While Treasurer Curtis Loftis avoids a recommendation to be removed from office, behind the scenes, the embattled statewide elected official had to be stopped from publishing potentially compromising financial information.

On April 4, Loftis was planning to publish a 600-page report that included a list of state agency funds, their cash balances, along with account numbers and sub account numbers, said state Sen. Larry Grooms, R-Berkeley, who has been leading an investigation by a Senate Finance Committee panel.

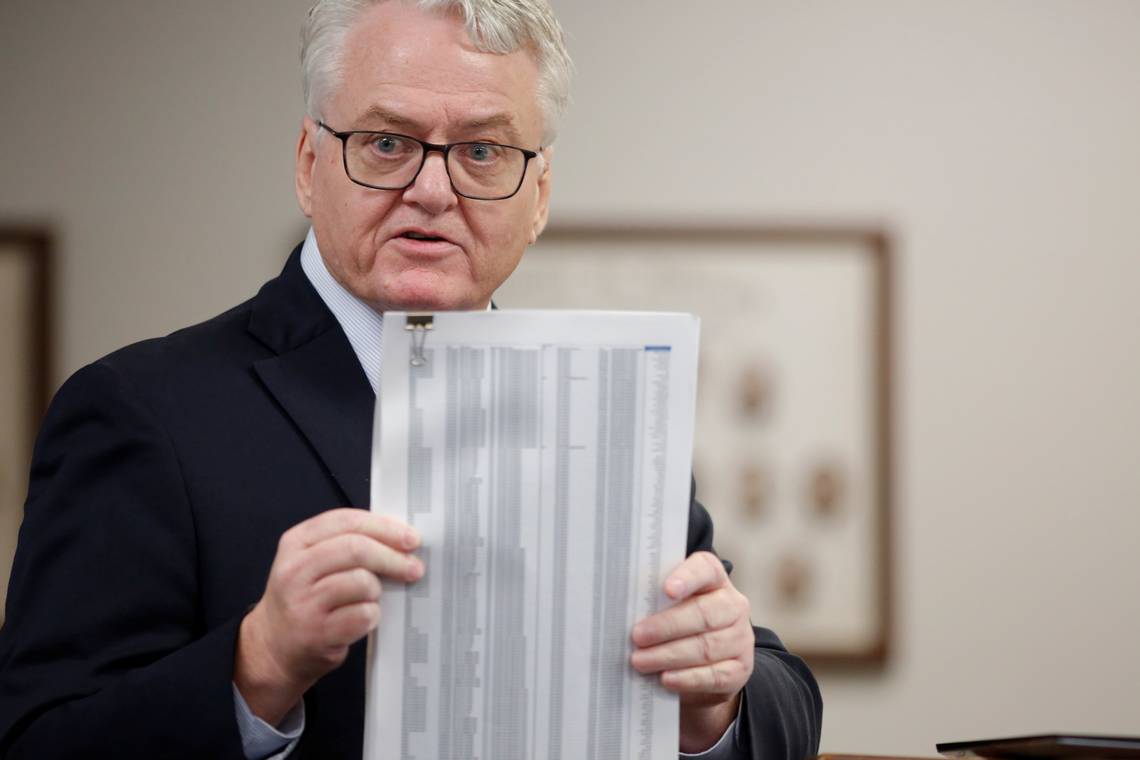

Grooms disclosed the detail Tuesday on the Senate floor while presenting a report of his panel’s investigation.

The treasurer’s plan to release the “highly sensitive” information, calls into question his current judgment and temperament,” Grooms said on the floor Tuesday.

Posting the report would have left the state severely vulnerable to cyber attacks.

Two days after a contentious hearing, Loftis notified lawmakers and others of his intentions. The move led to a scurrying around the state house, an emergency meeting among the state senators investigating the existence of a $1.8 billion account, an unplanned executive session of the state Senate, and a phone call between Loftis and Gov. Henry McMaster, who had knee surgery that morning.

McMaster convinced Loftis to stand down.

The state attorney general’s office was prepared to file paperwork with the state Supreme Court to stop Loftis from making the move. The chief of the South Carolina Law Enforcement Division also was involved in preventing Loftis from taking action.

During the April 2 contentious hearing in front of a Senate Finance committee panel, Loftis was asked if he was complying with state law, which requires public notice of how much money was in each of the state’s funds, and the names of banks money is deposited.

Loftis said he was not. He said during the meeting he would post an 80-page report online with those details, but previously shied away from it because he was afraid of potential cyber attacks.

“It has never been anticipated that each fund had to be listed,” Loftis said during the hearing.

Loftis said it would be an invitation for anyone who wants to hack the state.

“You might think somebody in Kiev would be interested to know what account $4.6 billion is in. If you would like this published, senator, we would publish it tonight,” Loftis said when saying the report included specific account numbers. “It is the architecture of the state’s treasurer’s office.”

Grooms during his presentation that the subcommittee was not asking Loftis to post the specific report.

“Members of the subcommittee made it clear they were not instructing him to publish such detailed information,” Grooms said.

The law is old and the term fund meant accounts in the early 1900s. But the law remains in place.

“The General Assembly has never changed a law for me,” Loftis said at the hearing. “I have asked repeatedly and I have never had a statute, even in other roles that I’ve had changed for me.”

But instead he intended to publish a more detailed 600-page report and even went as far to ask Department of Administration Executive Director Marcia Adams for a threat assessment if he were to take the action.

“We believe the statute requires actually a by agency, by fund reconciliation, which the treasurer’s office to my understanding is not doing currently,” state Sen. Thomas McElveen, D-Sumter, said at the hearing.

In a letter to Grooms on April 4, Loftis sought to clarify his comments at the meeting and wrote he thought the comptroller general and General Assembly had re-interpreted certain statutes and created “new and different disclosure obligations.”

“When I stated in the hearing that the state treasurer’s office is not in compliance with these reporting requirements, I meant that my office had not yet had the opportunity to change its reporting procedures in accordance with the re-interpretation articulated to me at the hearing,” Loftis wrote. “We are now working toward devising a secure means of complying with these new disclosure obligations.”

The disclosure of these actions take place as a Senate Finance panel has investigated the existence of a $1.8 billion account and why lawmakers weren’t notified sooner, and why no one knows which agencies or funds the money belongs. The account was created in 2017 when the state switched to a new accounting system. The account was meant as a flow through account and was supposed to have a zero balance at the end of a fiscal year.

But more than $1 billion remained and people in charge managing the state’s money did not know who was entitled to the cash. Lawmakers did not learn of its existence until last year.

In an interview during a break from the hearing, Grooms said Loftis should have come to lawmakers if there were any problems.

The last year Loftis’ office did a reconciliation by fund by account was in 2016, and the state did not have any money that was “homeless,” Grooms said.

“The State Treasurer’s Office reconciles its custodied bank and investment accounts to the General Ledger on a regular basis, according to schedule,” the treasurer’s office posted on its website in response to the hearing. “The reconciliations are performed daily, weekly, and/or monthly, depending on the bank or investment account.”

Loftis has argued that state auditors and the comptroller general knew about the account for years as well and they could have raised the alarm bells. But Loftis is now being blamed by the members of the Senate.

Lawmakers however did learn about the account until last year when new Comptroller General Brian Gaines, who was appointed last year, brought it to lawmakers’ attention.