After Fran Smith vanished in 1991, her husband’s dark secrets began to unravel.

In the three decades since, John Smith, 73, was convicted of killing his first wife in Ohio years earlier, in a murder authorities weren’t even aware of until they began investigating Fran’s disappearance.

Fran’s body has never been found, but prosecutors in New Jersey charged her husband in her death five years ago. Then the case took an unusual turn: Those same prosecutors dropped the murder charge against Smith in exchange for information her family and the FBI agent who spent years investigating the cases said is unreliable and likely untrue.

For more on the case, tune in to “Chameleon” on “Dateline” at at 9 ET/8 CT tonight.

In this first interview about the deal, retired FBI special agent Robert Hilland called out prosecutors for the arrangement.

“This was a failure on the part of the Mercer County Prosecutor’s Office,” Hilland told “Dateline.”

“They hung our family out to dry,” said Sherrie Davis, Fran’s sister.

The prosecutor’s office defended the decision to dismiss the charge, with a spokesperson saying in a statement that because a judge blocked prosecutors from introducing key evidence, what remained would have allowed them to “paint Smith as a bad husband but not a murderer.”

The spokesperson added that Fran’s family was informed of the likely dismissal and agreement before the charge was dropped on July 6, 2023.

“They acknowledged their understanding of how we were proceeding and, although disappointed in the outcome, did not express any criticism at that time,” the spokesperson said.

A spokesperson for the public defender’s office that negotiated the agreement for Smith would not comment.

‘Yes, I lied’

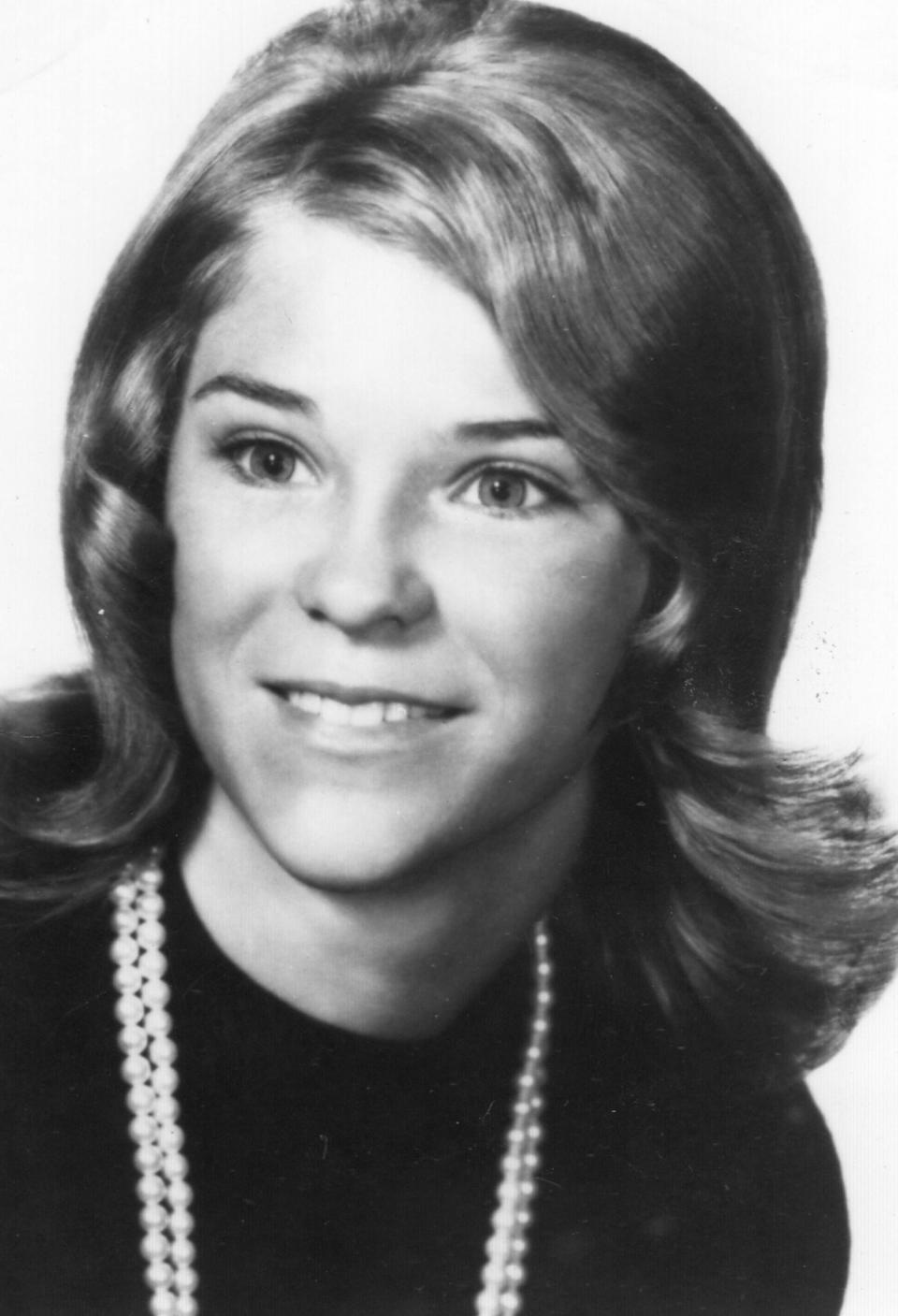

Fran, 49, disappeared on Sept. 28, 1991. The paralegal had recently moved from Florida to a condo in West Windsor, New Jersey, with her new husband, John Smith, and was recovering from a broken hip, her daughter, Deanna Childers, told “Dateline.”

Smith, an engineer, told authorities that his wife abruptly left to visit relatives, according to a West Windsor detective who investigated the case, Mike Dansbury. Her family said they hadn’t heard from her, however, and while relatives tried to piece together what happened, a detective revealed something Fran’s family hadn’t previously known: Smith had been married before.

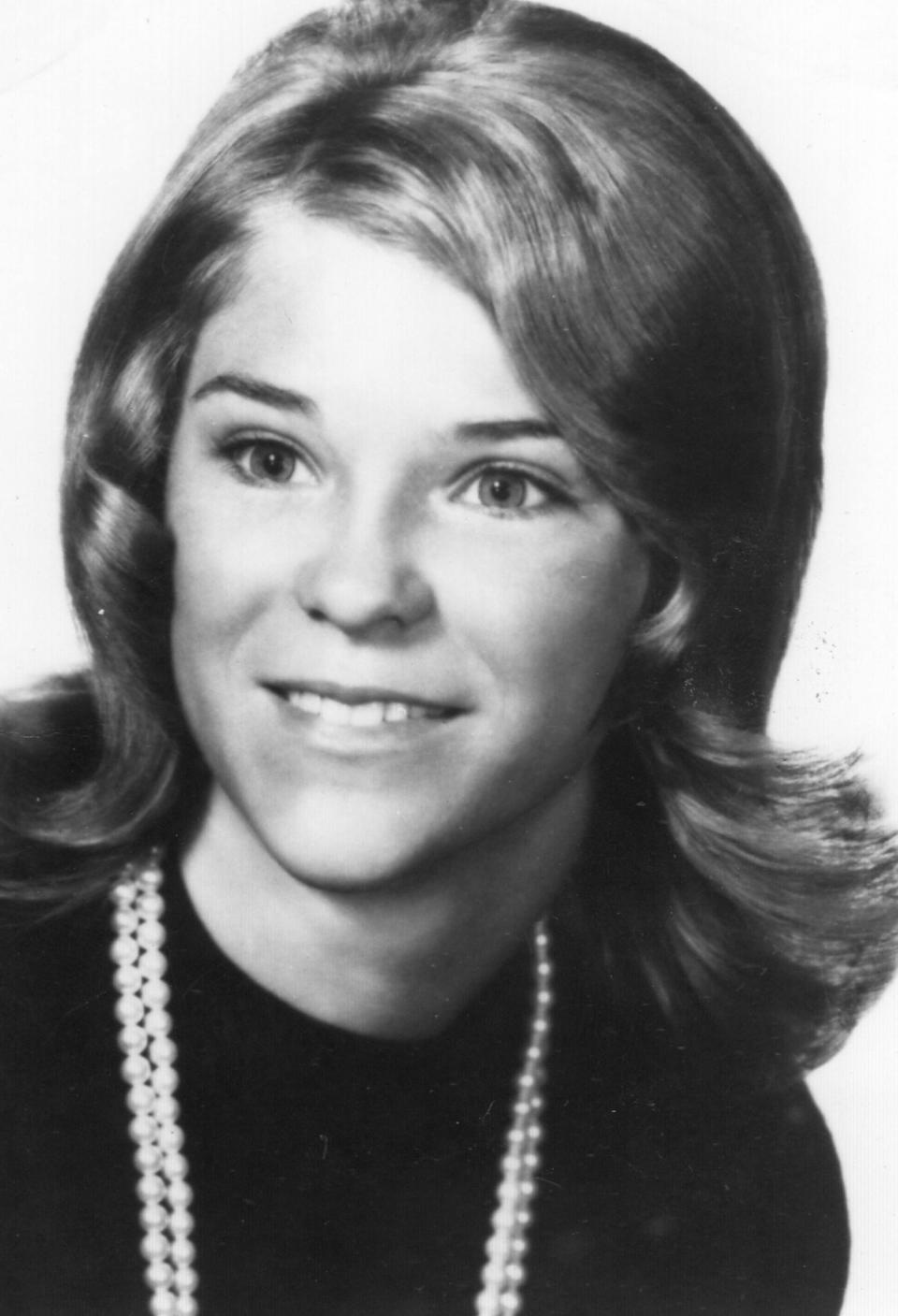

Decades earlier, he’d eloped with Janice Elaine Hartman after high school, another detective, Dave Mansue, told “Dateline.” But the couple split in 1974, after only a few years.

After tracking down a relative of Hartman’s, the family learned an even more startling detail: Days after they divorced, Hartman disappeared and was never heard from again. Authorities in Ohio believed she was a runaway and didn’t pursue the case as a possible homicide, Mansue said.

Smith offered strangely similar accounts and details in the disappearances of both wives, the detectives found. In a missing person’s report, Smith said he believed Hartman had gone to Florida with a red suitcase, Dansbury said. In Fran’s disappearance, he said he believed she’d gone to Florida to visit family with a yellow suitcase, Dansbury recalled.

When Fran disappeared, authorities discovered that Smith had a long-time girlfriend — an HR manager he’d met while applying for a job — living at a Connecticut beach house he owned. Frank Barre, a detective with the Milford Police Department who began assisting in the investigation, recalled that the girlfriend didn’t know that Smith had been married twice. Nor did she know that both women had disappeared.

“Her whole world was upside down,” Barre told “Dateline.”

The girlfriend agreed to call Smith and allow investigators to listen in and record the conversation.

She confronted him about his relationship with Fran, according to audio of the call, and asked if she was dead. Smith told her he didn’t think so but — because he didn’t know where she was — “they think I must have hurt her,” according to audio.

When she asked about Hartman, he said they’d divorced and he’d reported her missing. He said he’d only just learned that she’d never been found, according to the audio.

When she asked if he’d lied during a police polygraph test, he said: “I failed it.”

“Wait, John,” she said. “Did you lie during the test?”

“Yes, I lied during the test,” he said.

A long-held secret revealed

Investigators suspected that Smith was responsible for the disappearances of his wives, but didn’t have proof. It wasn’t until years later, after Hilland took over the investigations in 1998, that authorities got a break.

By then, Smith had moved to suburban San Diego, remarried and was working for a car maker. On May 5, 1999, Hilland organized an effort with FBI agents across the country to carry out a series of coordinated interviews with people linked to Smith — relatives, colleagues and exes — and with Smith himself.

During an hourslong interview with Smith, Hilland said he repeatedly confronted him about inconsistencies in his accounts of what happened to Fran and Hartman. When the agent confronted him about lying on the polygraph, Smith denied making the comment, Hilland said.

“I pulled out the tape recorder, hit play, and John could hear in his own voice all those things that he had said,” Hilland said about playing the taped conversation between Smith and his onetime girlfriend. Smith “turned beet red and shrugged his shoulders.”

At one point, Hilland said, Smith offered a hypothetical about two people having an argument and one of them being fatally struck by a bus.

Smith asked, “Is the other person responsible for a murder?” Hilland said. “We said, ‘No, that’s an accident. That would not be a murder. Is that what happened to Fran?’ He said, ‘I don’t know what happened to Fran. I just know she isn’t dead. If she’s dead, she’s probably in heaven.”

Smith told investigators he was having a heart attack, and the interview ended, Hilland said. But days later, the former investigator said, Smith’s brother shared something with the FBI that he hadn’t previously disclosed.

In exchange for an agreement that barred prosecutors from charging him, the sibling revealed that in November 1974 he’d seen Smith with a large plywood box in a garage next to his grandparents’ house in Ohio.

Smith was crying, Hilland recalled the brother saying, and appeared to be placing clothes that he believed belonged to Hartman in the box.

The box, which had been nailed shut, remained in the garage for five years, until his grandfather pried it open, Smith’s brother told investigators. The brother said he saw what appeared to be Hartman’s remains inside the box, Hilland said.

Her legs had been removed and her hair appeared to be rainbow-colored — a detail authorities later attributed to clothing dye bleeding onto her body, Hilland said.

The discovery haunted the sibling for years, Hilland recalled, but he hadn’t come forward because his grandfather had asked him to stay silent.

“The grandfather said, ‘If we call the sheriff, this is gonna cause your grandmother to die,’” Hilland recalled the sibling saying.

After the brother called Smith and told him he’d found the box, Smith arrived at the grandparents’ home, put the box in the passenger seat of his Corvette and drove off, Hilland said the brother told officials.

After his revelation to the FBI, Smith’s brother agreed to confront his sibling. In the conversation, which was recorded, Smith described the box as a “joke” and said someone had dropped it off with a dead goat inside, according to a transcript of the call.

At one point, the brother said: “I had nightmares where Jan chased me down the road, beat me with her legs, John.”

“OK,” Smith replied.

Nearly a year later, remains were exhumed from a rural Indiana cemetery and, in April 2000, positively identified as belonging to Hartman.

Years earlier, it turned out, a road crew had found the box described by Smith’s sibling in a roadside drainage ditch, but the remains couldn’t be identified and the body was buried in what Hilland described as a Jane Doe grave.

Six months after the identification, Smith was charged with murder in Hartman’s killing. He pleaded not guilty and was convicted at trial. In 2001, Smith was sentenced to 15 years to life in prison.

The case falls apart

After that conviction, Hilland continued searching for Fran. He said he organized multiple excavations at Smith’s workplace in New Jersey and the Connecticut beach home, and he worked with undercover informants at the prison where Smith was incarcerated to try and gather information. Neither efforts yielded evidence, he said.

Prosecutors from Mercer County later met with Hilland at the FBI Training Academy in Virginia, where he was working as an instructor. Although there was no new evidence, the prosecutor’s office said in its statement, after the meeting, they believed they had enough to charge Smith in Fran’s 1991 disappearance.

In November 2019, Smith was indicted on a charge of first-degree murder after prosecutors presented evidence to a grand jury about both Fran’s disappearance and Hartman’s killing.

“It was the state’s position that, in 1991, Smith believed he had a successful blueprint to get away with murder and followed his 1974 playbook but corrected the only mistake he made in the murder of Janice Hartman — keeping her body in a place where it would be accidentally discovered,” the prosecutor’s office said.

But in 2022, the statement said, a judge barred prosecutors from presenting evidence from Hartman’s murder, ruling that it would unfairly prejudice the jury. Faced with the impending dismissal of charges, the statement said, prosecutors entered into an agreement with Smith.

Because Fran’s body had never been found, the statement said, the likelihood of uncovering new evidence and pursuing a successful prosecution appeared “minimal.” To provide closure for the family, the statement said, prosecutors agreed to drop the murder charge if he revealed what he did with Fran’s remains.

The prosecutor’s office didn’t require corroborating evidence to back up the account — “recovery” would have been impossible given how long ago she disappeared, the statement said — nor did they require Smith to say how he killed her.

“In negotiating the non-prosecution agreement, Smith would not admit to the murder but would agree to tell us what he did with her body,” the spokesperson said in an email.

Prosecutors shared what Smith said with Fran’s family but didn’t reveal the details publicly, according to the statement. Deanna Childers, Fran’s daughter, told “Dateline” that officials told the family that Smith confessed to wrapping her mother’s body in a blanket and leaving her in a dumpster at the factory where he worked in New Jersey.

Davis, Fran Smith’s sister, said the idea that the deal provided closure for her family was an insult. She didn’t believe Smith’s account, she said, adding that the information did “nothing” for her family.

Hilland, who retired from the FBI in 2022, was outraged that the deal didn’t require a full confession or corroborating evidence. He said it seemed highly unlikely that Smith would have left Fran’s body in a trash bin at a factory with many employees who easily could have noticed.

To Hilland, there was so much circumstantial evidence implicating Smith in Fran’s alleged killing — including when he told his then-girlfriend in the recorded call that he lied to police while they were questioning him about Fran’s disappearance — that he believed prosecutors could have proven his guilt.

“Shame on them for accepting” his account, Hilland said, “because now they’ve given him immunity based on that.”

Hilland added that when John Smith goes for his next parole hearing in 2029, he may have a better chance of getting out because he can say he cooperated with authorities.

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com