The $6.4 billion bond measure — which overhauls how the state addresses the overlapping crises of homelessness, drug addiction and untreated mental illness — passed late Wednesday by the thinnest of margins, barely 30,000 votes in a state of nearly 40 million people.

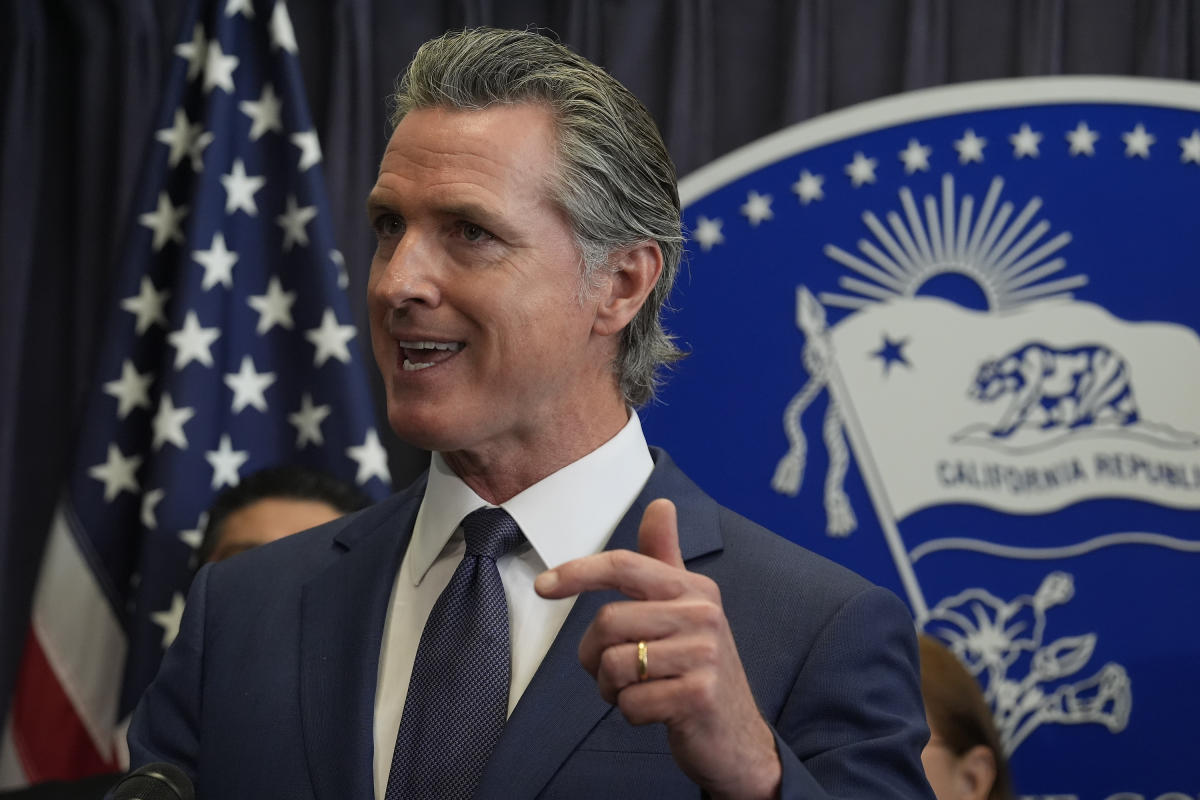

Newsom, who made Prop 1 the centerpiece of his political agenda this year, celebrated the win Thursday but acknowledged the obvious message from voters.

“People want results. People are exhausted with the time delay,” the Democratic governor said at a news conference in Los Angeles hours after a painstaking, two-week count to settle the race. “They’re exhausted with the promises. They want to see results.”

The unexpectedly close result, in a campaign that featured only token opposition, shows that Californians are deeply divided over whether to spend more money on homelessness, and to deal with the cost of housing more broadly, which voters consistently say is the No. 1 issue in a state with more people living on the streets than any other. It also raises questions about Newsom, and whether he can execute on major policy proposals.

Californians Against Prop 1, the ragtag group of volunteers who were the sole voices against Newsom’s campaign, said in a statement that the measure could constitute a “humanitarian disaster.”

“Prop. 1 is not a ‘huge’ win for Gov. Newsom. It’s an embarrassing squeaker of a victory that contains a strong warning,” the group said after the race was called.

A map of the election results illustrates the point vividly, with Prop 1 winning along the liberal coast and losing just about everywhere else — especially in the more conservative inland parts of the state. Homelessness, which surged during the pandemic, is most visible in cities such as Los Angeles and San Francisco but is at record levels across California.

The state has spent more than $12 billion over the last five years to address the problem, clearing thousands of encampments and moving people into housing, but the close Prop 1 vote suggests a deep reluctance to spend more.

“I get why people said ‘I’m not going to support another bond,’” Newsom said Thursday.

Prop 1 was Newsom’s big swing at housing and homelessness — a sweeping measure that could help define his legacy, or tarnish it, if he seeks higher office.

The measure is more than an anti-homelessness effort. It redistributes spending from a tax on incomes over $1 million, which was adopted by voters in 2004, to focus more on treating severe mental health problems — in part by building facilities to replace those closed decades ago by then Gov. Ronald Reagan.

Critics charged that this overhaul would short-change existing programs for less severe mental health — the kinds of conditions that can lead to more serious problems, and homelessness. They also raised concerns about compulsory treatment — but the opposition raised almost no money to counter the governor and his allies.

As the Prop 1 funding rolls out, starting later this year, the counties that fund the bulk of mental health treatment in the state will face new mandates to direct more services toward housing and to treating people experiencing homelessness.

That’s a feature, not a bug, in Newsom’s mind. He has reasoned that forcing counties to focus more on people on the street, and only on programs that really work, will help deliver the results voters are demanding.

Going to the voters with a bond measure is always risky and especially so during a primary, when the electorate tends to be older and more conservative. That lesson was driven home hard in recent days.

Ahead of the March 5 primary, the campaign predicted the measure would pass with around 55 percent of the vote. Passing with 50.2 percent, it underperformed even those low expectations.

It spent the past two weeks in limbo, though it faced almost no paid opposition. Ten days after the election, the yes campaign sent out a plea for supporters to help fix rejected ballots to push the measure over the finish line.

That’s all despite the fact that Newsom marshaled an unprecedented coalition of supporters — featuring Republican and Democratic leaders from across the state, along with police and fire officials and mental health organizations. The “yes” campaign raised $20 million, compared to just $2,000 by the opposition.

Newsom endured post-election criticism for risking the measure by placing it on the March ballot. His response is that he had no choice, addressing an urgent matter in a way that will start channeling money into the issue by October.

In the end, even a narrow victory is a win. Newsom acknowledges that voters sent a flashing yellow warning sign with the results — and that they may not be willing to spend more money on homelessness any time soon.

“I’ve never been associated with something I’m more proud of,” Newsom said. “I recognize now the imperative of delivering on this vision.”