The event, known as a nova, will be a once-in-a-lifetime skywatching opportunity for those in the Northern Hemisphere, according to NASA, because the types of star systems in which such explosions occur are not common in our galaxy.

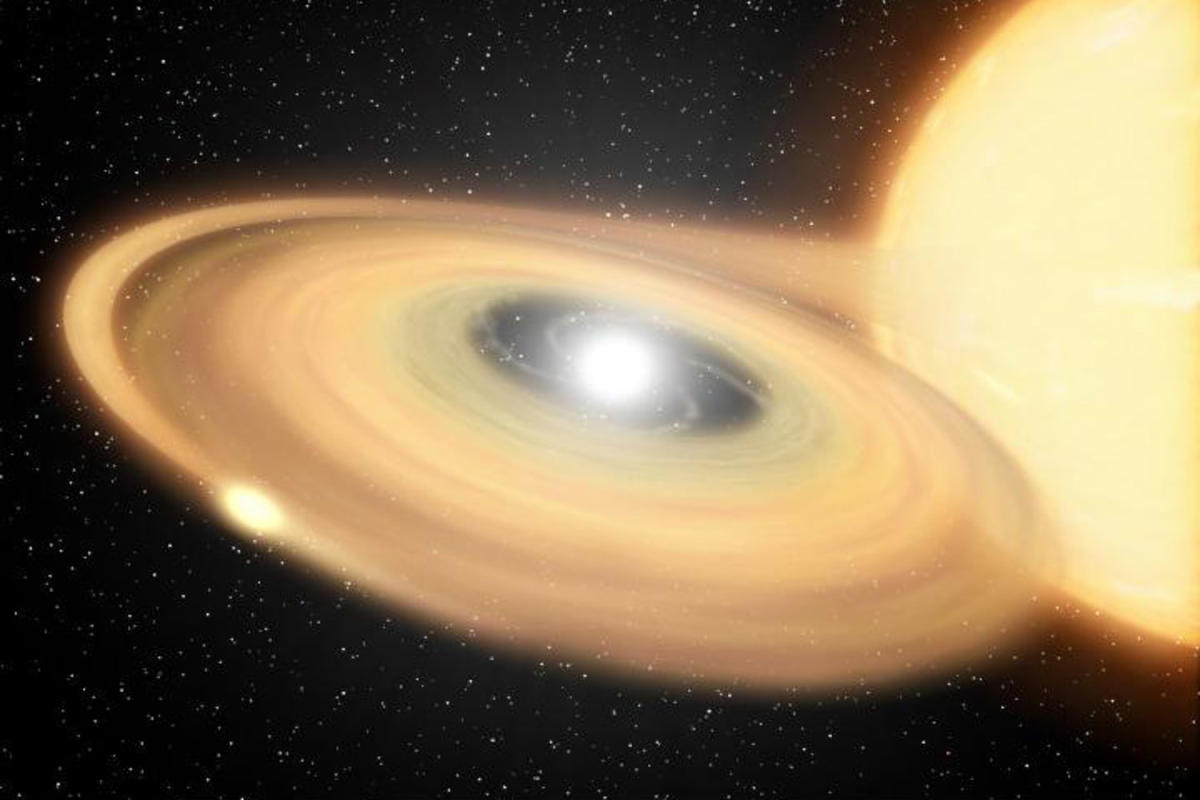

The stellar eruption will take place in a system called T Coronae Borealis, which is 3,000 light-years away from Earth. It contains two stars: a dead star, also known as a “white dwarf,” closely orbited by a red giant. Red giants are dying stars that are running out of hydrogen fuel in their cores; the sun in our solar system will eventually become one, according to NASA.

In systems like T Coronae Borealis, the two stars are so near to each other that matter from the red giant is constantly spilling onto the surface of the white dwarf. Over time, this builds up pressure and heat, eventually triggering an eruption.

“As matter accumulates on the surface of the white dwarf, it heats up and you get higher and higher pressure until bang — it’s a runaway reaction,” said Bradley Schaefer, a professor emeritus of physics and astronomy at Louisiana State University.

He likened the nova explosion to a hydrogen bomb detonating in space, adding that the resulting fireball is essentially what people will be able to see from Earth. (A nova is different from a supernova explosion, which occurs when a massive star collapses and dies.)

At its peak, the eruption should be visible to the naked eye, Schaefer said: “It’s going to be bright in the sky, so it’ll be easily visible from your backyard.”

Astronomers predict that the nova explosion could happen anytime between now and September. The last time this particular star system erupted was in 1946, Schaefer said, and another eruption will likely not occur for another 80 years or so.

Astronomers around the world are monitoring activity in the T Coronae Borealis system. Once an eruption is detected, Schaefer said, the best and brightest views will likely come within 24 hours, when it reaches roughly the same brightness as the North Star. The outburst may remain visible to the naked eye for a couple of days before it begins to fade.

Even after it dims, skywatchers will likely still be able to spot the eruption for around a week using binoculars, according to NASA.

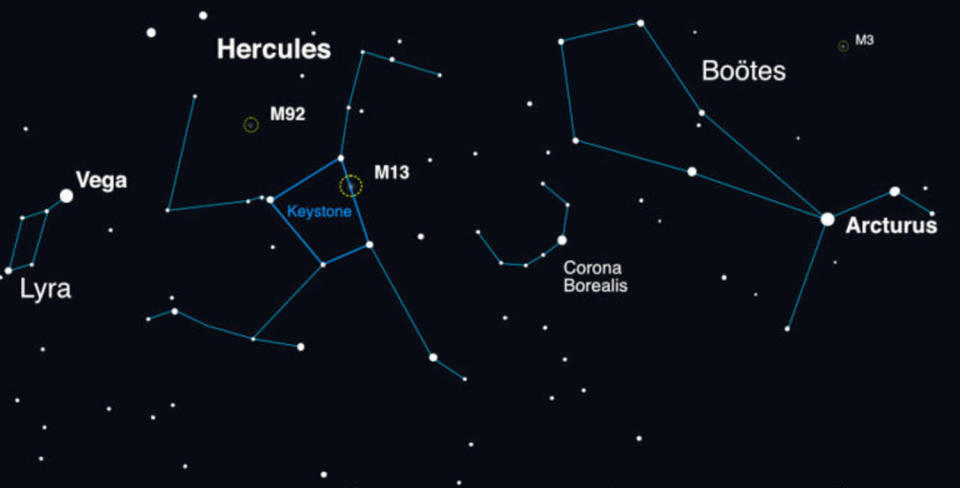

The T Coronae Borealis system is normally too dim to see unaided, but skywatchers can find the outburst by locating the constellation Corona Borealis, or the Northern Crown. The constellation will appear as a small, semicircular arc between the more widely recognizable constellations of Hercules and Bootes.

Schaefer, who has done extensive research on the T Coronae Borealis system, said it’s worth trying to catch a glimpse.

“This system happens to have a recurrence time scale under a century, but most of them have cycle times longer than 1,000 years or so,” he said.

In a paper published last year in the Journal for the History of Astronomy, Schaefer discovered two “long-lost” T Coronae Borealis eruptions in historical records — one documented by German monks in the year 1217 and another seen by the English astronomer Francis Wollaston in 1787.

“These monks near Augsburg, Germany, didn’t know what it was at the time, but they highlighted the eruption as being one of the two most important events of the year,” Schaefer said. “They called it in Latin ‘signum mirabile,’ which translates to ‘wonderful omen.’ It was thought to be a good sign.”

But pinpointing the exact time when skywatchers will have a chance to see this “wonderful omen” is tricky business.

“It could maybe even happen tonight,” Schaefer said. “More probably it’ll be within the next couple of months, and very probably before the end of summer.”

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com