After more than 80 years buried alone, a Fresno County teen was recently exhumed and set off on a 1,700-mile journey to be buried with family — a better ending to a tragic story.

The family of Eric Cummings, who was killed in 1941 in Sanger, set out about six years ago to move the long-dead teenager from Sanger Cemetery to be buried with his parents near Everton, Missouri. It wasn’t an easy task, they said, between restrictions in California over COVID-19 and the Sanger Cemetery’s rules about exhumations.

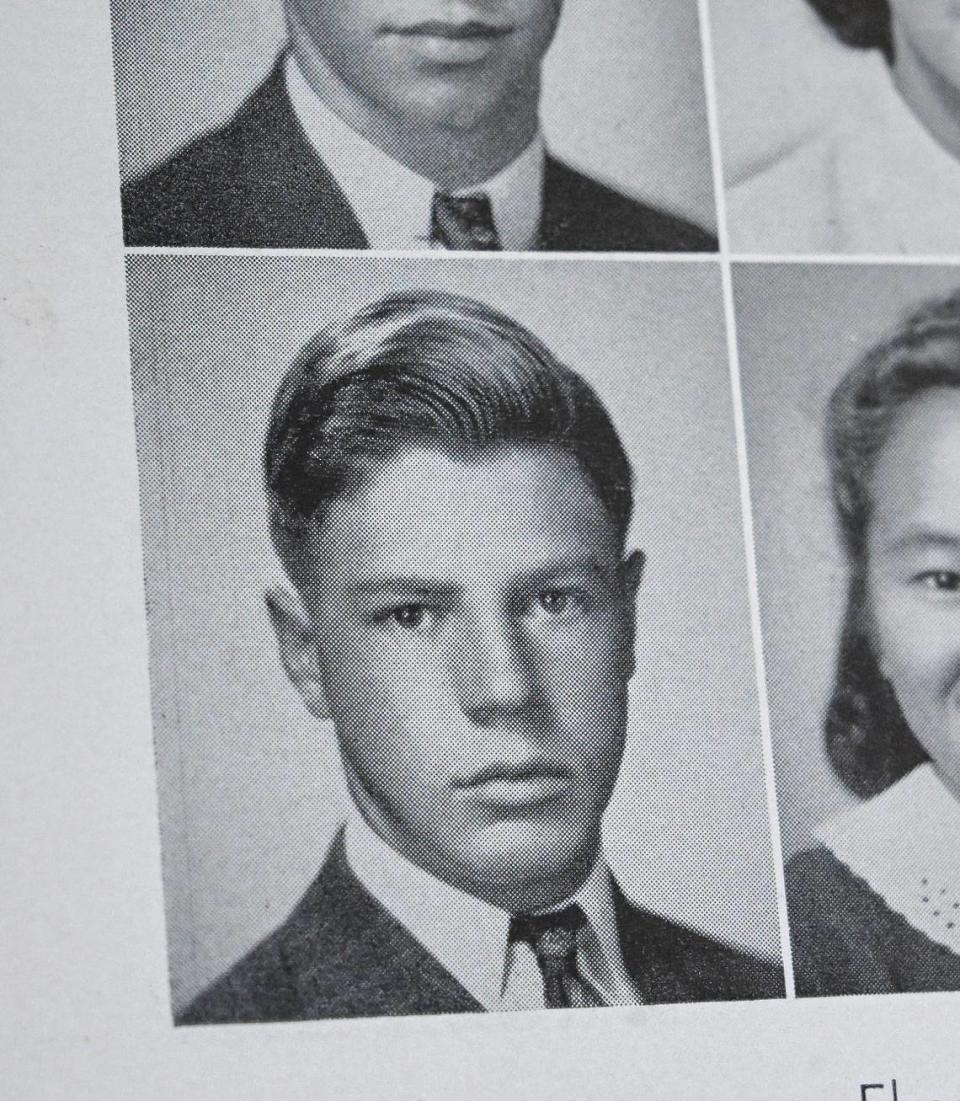

Eric Halbert Cummings, 18, was buried Jan. 15, 1941, three days after he was found dead near Mount Campbell between Sanger and Reedley, according to Fresno Bee archives.

Law enforcement officers at the time determined the Sanger High senior had been shot to death while out on a walk, archives showed.

Eric’s parents, Roy and Minnie Cummings, could not make it to the funeral in 1941 because they didn’t have the money. Eric had moved to Sanger with his sister and brother-in-law because times were hard and they were looking for opportunity, said Barry Cummings, Eric’s nephew.

Sanger High students attended the funeral, archives say.

Cummings earlier this month drove out to pick up the uncle he never met and transport the remains to Liberty Cemetery near Everton, Missouri, to be buried with the teen’s parents and some other family.

“It’s just that’s where he belonged, and even though it doesn’t — in the big scheme of things — it doesn’t matter. You know, he’s just bones, (but) he’s not there,” Cummings said.

What happened to Sanger teen found dead?

Eric Cummings went out on a walk on Jan. 12, 1941, a Sunday, but didn’t come home, Bee archives and Cummings family members said. Initially, investigators thought he suffered a hemorrhage, but an autopsy turned up a bullet wound.

Investigators in 1941 told The Fresno Bee evidence at the scene showed Cummings appeared to be sitting on a rock while wearing a neutral-colored moleskin jacket and shirt, which could have made it difficult to see him.

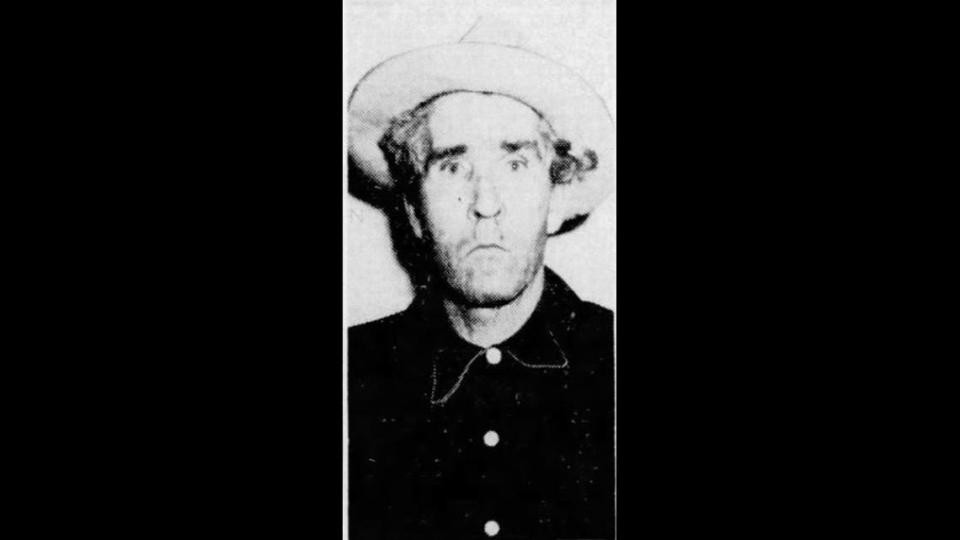

Cal Self, a 66-year-old stableman, was in the area around Campbell Mountain from about 10 a.m. to noon on the day of the shooting while looking to hunt coyotes, he told police. He said he did not see Cummings before or after firing a single round.

“I only fired one shot and that was at a hawk,” he said, according to the Jan. 14, 1941, edition of The Bee. “If that shot hit the boy, I didn’t know anything about it because I didn’t have any idea there was anyone on the mountain.”

Investigators said Cummings was not killed instantly, but rather the bullet appeared to have entered just below his chin, struck a vertebrae and came to rest in his left shoulder.

He searched for a way to climb down the rock but ultimately jumped down, police said evidence showed, before he walked about 50 feet and collapsed. He died of shock and blood loss, the coroner at the time found.

A search party found him after the teen was reported missing. Self, the stableman, participated in that search before he was publicly noted to be involved in the shooting, according to a Bee article.

Ann Hasenbalg, a niece to Eric and sister to Barry Cummings, said the family in Missouri received a letter from the man who fired the rifle.

“He put in an envelope $5, and said he was really sorry but that’s all he could pay,” she said in a phone interview. “It’s just a tragic story.”

Recklessly discharging a weapon was apparently an issue at the time, leading law enforcement officials to call for potential legislation.

Cummings was the second person killed by an errant bullet in Fresno County that week after 11-year-old Robert Rowland was killed in Worthan Creek Bed in Coalinga four days earlier by an apparent stray bullet.

Moving remains from the cemetery

Moving a body at the Sanger Cemetery on Rainbow Route is rare, according to Ken Sonksen, the general manager.

He estimated it has happened on 10 occasions at the graveyard where he has worked since 1998. That has included moving a body from Sanger to another burial place in Fresno County or even across Rainbow Route, which bends to the south and splits Sanger Cemetery in two.

Cummings said he started trying to get his uncle moved about six years ago and over the years saw a series of fits and starts. He said he got his sister Ann involved and she started making calls.

“I don’t know if that’s why it started going. She can be scary,” he said. “She scares me and I’m fearless. I don’t know if that’s (why). It certainly didn’t hurt.”

Hasenbalg said she had become frustrated by the process with the cemetery that did not seem complicated.

“They’re nice and decent and we have been to them, but it’s been some time,” she said. “We just want to bring him back.”

The Fresno County Public Health Department said through a spokesperson they only require a $12 fee and an application for approval to remove remains. Assuming the paperwork is filled out correctly, the permit is typically granted the same day.

The Sanger Cemetery generally does not do an exhumation during the heat of the San Joaquin Valley’s summer, according to Meggin Boranian, an attorney for the Sanger/Del Rey Cemetery District. Disinterments are also a lower priority than burials and other cemetery needs.

She pointed to COVID-19 as an unusual circumstance the cemetery was dealing with in recent years.

“They did their best to accommodate the family,” she said. “There was a time during COVID they didn’t do disinterments.”

How do you transport remains?

Cummings said on the day he picked up the remains he got a call the previous week to come get his uncle. Retired from his technician job in telecommunications, Cummings left to make a drive that took about three days from his home in Molt, Montana, he said.

He said he did not expect to be carrying a casket with the intact skeleton of his uncle in the back of his SUV.

He had envisioned moving cremated remains or whatever smaller amount of remnants that had not decomposed. Staffers at the cemetery told him not to expect much to remain after 83 years.

But, then he learned days before his trip to Sanger that Eric’s intact skeleton wearing a his dress suit had been exhumed all the way down to his finger bones and still-combed hair. A comb remained in his shirt pocket.

“When they dug him up, he’s intact — no smell, no nothing. So he’s intact now still,” Cummings said. “So he did his part to stay together, so we will do our part keeping him together. After all that time (to) grind him up and burn him — it’s not right.”

So Eric was placed inside of a new casket and loaded into Barry Cummings’s Chevrolet Suburban for the trip to his final resting place.

Cummings said on April 16 his trip east went smoothly — aside from the hot coffee he spilled in his lap while driving. The crew in Missouri had started digging before he arrived and his uncle was buried next to his parents the previous day.

As well as visiting family along the way, he said he stopped at two cemeteries in Kansas where Eric’s brother (Barry’s dad) and his grandparents are buried.

Family and friends have already been asking if he peeked inside the coffin — he didn’t — and if the trip with remains in a casket was creepy.

“It wasn’t at all. It was very comforting right off the bat,” he said. “Being around him, it just seemed very peaceful.“