It’s been more than three years since the Miami city commission approved a comprehensive plan to restore the historic yet long-shuttered Miami Marine Stadium. Eight years since the commission authorized $45 million in bonds, never issued, to fund its renovation.

Ten years since Jimmy Buffett headlined a fundraiser with Gloria and Emilio Estefan, fellow veterans of the stadium’s floating barge-turned-stage, to support a campaign to save the place. Buffett,who in 1985 gave one of the stadium’s definitive performances before jumping in the water, died last year without a chance for an encore.

And it’s been 14 years since then newly elected Miami Mayor Tomas Regalado vowed to see the cherished city-owned stadium, widely regarded as a marvel of architecture and engineering, reopened before his time in office ended.

Yet today the assertively angular, raw-concrete stadium grandstand still visibly languishes on the edge of Virginia Key and the Rickenbacker Causeway, one foot on land and the other in the water — a uniquely situated design that likely could not be replicated today. Closed since 1992, fenced off and slathered in graffiti, the Commodore Ralph Middleton Munroe Miami Marine Stadium has been a victim, critics contend, of apathy and dysfunction by the city’s managers and commissioners.

But now a political shift on the five-member commission, and a new report that concludes a restored stadium would be a profitable and in-demand venue for concerts and performers, is breathing new life into the stalled effort to revive the 1963 landmark — which has now been shuttered longer than it was operating.

So can it finally happen? Reformist city commission newcomer Damian Pardo and Miami Mayor Francis Suarez believe so.

Armed with the report, Pardo, whose district includes Virginia Key, says he will push for the city to hire an operator, re-approve the expired bond authorization and prepare a 2025 referendum to win voters’ approval for the project. It’s long past time, Pardo said, to finally get moving on the renewal of what nearly everyone agrees is a quintessential slice of Miami.

“One-hundred million kazillion percent, I want to champion this project,” Pardo said in an interview. “If there is a project that has Miami written all over it, it’s this one. It’s iconic on a worldwide basis. And derelict. And that is exactly what needs to change in our city.”

The plan also has the full backing of Suarez, who has long supported the restoration and says he will now make it a priority as a legacy-defining project before his second and final term ends in 2025.

“We’ve done all the studying we need to do, and we’re bullish on it,” Suarez said in an interview. “It’s an iconic venue that can create an even more iconic view of our city around the world. And that’s what you want as the city continues to mature.”

Suarez’s active involvement could be critical, Pardo and other supporters say. The mayor said he will lobby members of the commission individually. He also got the city administration to move forward with the consultant’s report after the contract for the study had been sitting without action for a prolonged period.

“He is fully invested now, I believe,” said Stuart Blumberg, the retired founding president of the Greater Miami Hotel & The Beaches Hotel Association, who had a hand in the creation of the Arsht Center for the Performing Arts and other major projects.

Read More: Photos of Miami Marine Stadium in its heyday

Still influential at 87, Blumberg has now spent two years persuading Suarez and the city to tackle the marine stadium.

“There wasn’t any great appetite from the city manager or anybody else to get this done,” he said. “It just gave me more impetus to move this forward. This is the last thing on my bucket list.”

Longtime supporters of the stadium’s renovation hope the changed dynamics mean the project can now win the necessary majority support on the commission that has been lacking in recent years.

“It’s drifted for years because we have not had a political and civic champion,” said preservationist Don Worth, who has been pushing for the stadium’s restoration since 2008. “These are complicated projects, and someone needs to take that on. I’m hoping it’s different now. This project is too good to give up.”

Upbeat consultant report

The report that’s helping fuel the renewed effort was commissioned by the city from AMS Planning and Consulting, a national firm that specializes in analyzing finances for cultural groups and facilities. AMS has worked with the Arsht Center in Miami and other major groups and venues across the country.

Given its unique location and expansive views of Biscayne Bay and downtown Miami’s skyline, AMS concluded, the 6,000-seat stadium would be a prime draw for performers and producers to rival legendary venues such as the Red Rocks Amphitheater outside Denver. AMS looked at Red Rocks and about a dozen other roughly comparable facilities across the country for its analysis, though it concluded “there is no analog” for the marine stadium anywhere else.

AMS recommended that the city hire an independent operator to run the stadium to reduce the risk and financial load for taxpayers. The report also said the independent operator deal could also include free use by the city for public events.

Its estimates show the reopened facility would initially break even and then generate a small profit for the city in its first decade of operation under conservative estimates. If ancillary revenue sources like city ticket surcharges that are now comparatively low are increased, parking revenues added and naming rights sold, the report says, the profits could increase significantly, though it doesn’t provide numbers.

Worth said the study confirms that previous analyses of the stadium had concluded, and said he knows of several prominent venue operators that are seriously interested in running it.

“There are experienced, successful organization that want to run the Marine Stadium, and that’s the acid test.” Worth said. “We’ve been saying for years the stadium would be a great destination venue. It’s great to have a consultant say the same thing. The city is finally going about this the right way.”

One-of-a-kind venue

The report doesn’t cover the cost of the contemplated bond issue, which would be borne by taxpayers. Project estimates now exceed $62 million because construction costs have risen since the previous renovation estimate was done. Blumberg, who was the originator of the bed and restaurant tax that has financed hotel, tourism and cultural and sports facilities across Miami-Dade County, said the stadium renovation would be an ideal use of the fund.

“It’s a historic venue, one of a kind in the country,” he said. “There is revenue that can make this a success. I would think it’s going to be a huge success. It is Miami.”

The bare-concrete marine stadium was designed by Hilario Candela, then a young Cuban exile, in collaboration with the late engineer Jack Meyer. Candela, a revered architect, died at 87 two years ago, still awaiting the promised revival of his masterpiece.

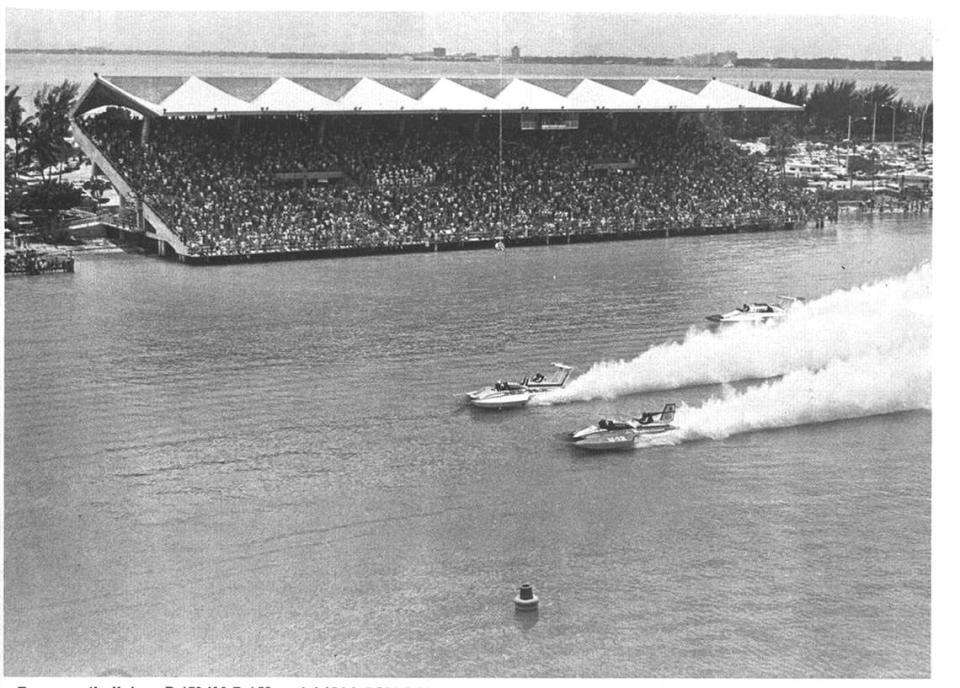

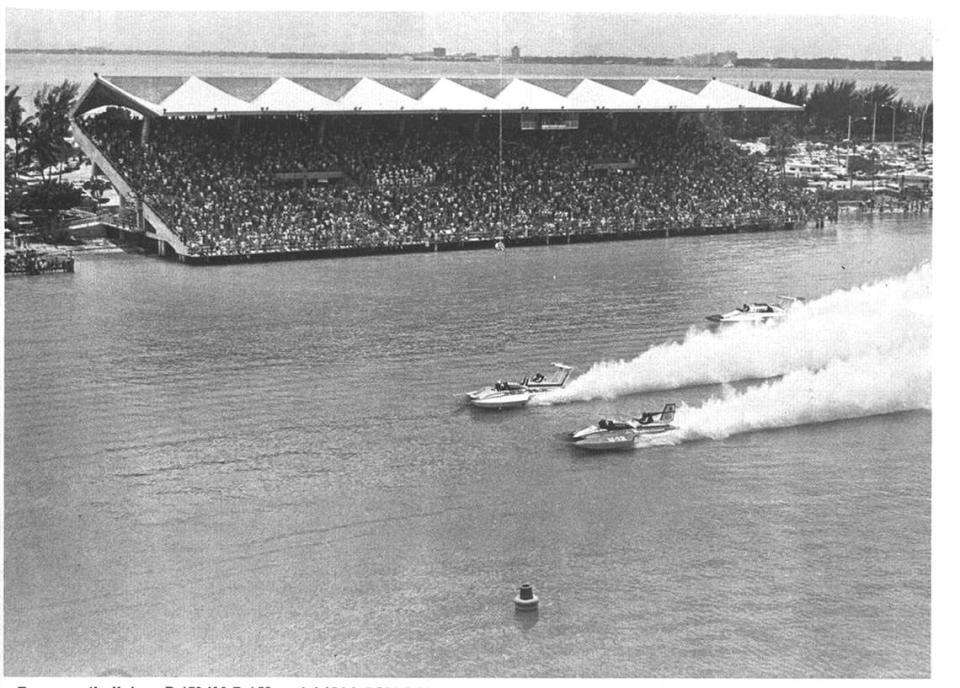

Inspired by works of Tropical Modernism and Brutalism from Cuba and across Latin America, Candela and Meyer came up with a daring vision: a vast cantilevered concrete roof canopy folded like origami and suspended over a 6,500-seat grandstand that juts over the water of a large artificial water basin.

Built by the city for powerboat races, the stadium quickly became the site of a wide variety of public gatherings and musical and artistic performances that took place on a converted barge lashed to the grandstand. Those ranged from popular Easter sunrise services to the filming of an Elvis Presley move and concerts by such stellar attractions as Ray Charles, Queen, the Beach Boys and the Miami Sound Machine. Buffett performed numerous times with his Coral Reefer Band.

But the city lost money on its operation and closed the stadium after Hurricane Andrew in 1992, misleadingly blaming damage from the storm. As numerous engineering studies since have shown, damage from Andrew was minimal. Candela and Meyer’s innovative stadium was so well designed and built, in fact, that it remains in remarkably sound structural shape despite decades of close exposure to saltwater, the studies show.

The administration of Mayor Manny Diaz eyed demolition for the stadium, but a coalition of preservationists, artists and activists managed to get the grandstand and basin designated as a protected historic site by the city in 2008. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2018.

And though Regalado while mayor identified substantial funding for the renovation, the project foundered, especially after the privately driven plan partly supported by the Estefans fell apart in 2014.

Two years later, the city hired prominent Miami architect Richard Heisenbottle, a specialist in historic preservation, to draw up a detailed plan for the stadium restoration. His blueprint includes extensive concrete restoration, as well as installation of new seats, sound and lighting systems, and a new floating stage.

The city has not entirely neglected the stadium. A $3 million project to repair corroded grandstand pilings that sit in the water, funded mostly by the Florida Inland Navigation District, was recently completed.

New commission dynamics

But shifting political dynamics on the commission meant majority support evaporated and money for construction has not been approved.

After the original bond authorization lapsed in 2021, the commission put off consideration of a nearly $62 million bond, reflecting increased costs, amid concerns over costs and the lack of an updated business viability study demanded by Commissioner Joe Carollo, who has expressed consistent skepticism over the stadium renovation.

Last year, Carollo joined with commissioners Sabina Covo and Christine King in a 3-0 vote to slash that bond amount to $6 million, and only for spending on a controversial nearby boat ramp and mooring field, not the stadium structure. The vote by Covo, who briefly occupied the seat representing Virginia Key, was a sharp departure from predecessor Ken Russell’s support for the project.

But stadium skeptic Covo is out of office after losing elections last year. Pardo replaced Covo. Alex Diaz de la Portilla lost a re-election bid after his arrest on political corruption charges. He gave way to another reformist, Miguel Angel Gabela. Carollo, meanwhile, appears to have lost some political influence amid a continuing scandal over his use of city authority to retaliate against Little Havana entrepreneurs who supported a political challenger.

Pardo and Gabela have since often voted in tandem, with Commissioners Manolo Reyes and Christine King often joining them as swing votes. Pardo said he doesn’t know where Gabela stands on the stadium, but believes his colleagues will now give the plan, backed by the findings of the new feasibility report, a fresh hearing.

“I’m very excited by these results. This could be a significant plus for the city,” Pardo said. “This is such a significant structure in some way to many in the community. We have suffered so much loss of identity in this community. So many historic structures have fallen by the wayside. It would be an honor to resurrect this one.”