Judd Blevins lost his seat on Enid’s six-member City Council by 268 votes, according to unofficial results from the Oklahoma State Election Board. Nearly 1,400 people turned out, about a quarter of Ward 1’s registered voters and hundreds more than voted when Blevins was first elected last year.

Blevins will be replaced by Cheryl Patterson, a former teacher and longtime Republican who campaigned on a return to “normalcy” for this small city nearly 100 miles north of Oklahoma City, which was divided by the furor over Blevins.

“We won,” said Connie Vickers, a Democrat in conservative Enid, who was among the first to publicly confront Blevins over his white nationalist ties. “Blevins lost. Hate lost.”

Blevins faced the recall vote after local activists learned that he had marched alongside neo-Nazis in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017 and led an Oklahoma chapter of the white nationalist group Identity Evropa.

Blevins has denied that he has ever been a white supremacist, but at a candidate forum last week he defended marching in Charlottesville and said his activism was motivated by “the same issues that got Donald Trump elected in 2016.”

Blevins had his supporters in Enid. A woman who campaigned for him said she liked what she saw from him over the last year. Another outside a polling station Tuesday said he knew Blevins personally.

“He’s a really good guy,” Tim McDonald said. “He deserves a second chance.”

Spotted holding a sign on a corner near his polling place, Blevins said he thought voters would rally to save his seat. “I’m pretty confident I’ll come out on top,” he said. “And if not, I fought the good fight.”

Blevins said that if he lost, he had no plans to run again. “I just go back to private life,” he said. “Life goes on.”

Blevins said in a statement Tuesday evening that the race had been “a trial not just for me, but for many in this community.” He added: “I have finished the race. I have kept the faith.”

The results reported Tuesday night are unofficial until they are certified by the Garfield County government, which is expected to happen as soon as Friday.

Earlier in the day, Patterson and a group of supporters held her campaign signs on a busy corner. Patterson said she felt good, aside from the frigid temperatures.

“I think the citizens of Enid know who I am, because I’ve been here for 40 years and been really involved in the community.”

She said she was looking forward to “a resounding message that Enid is a great place to be.”

She added: “Enid is not a town that promotes white nationalism or white supremacy in any way. And the people are good. And I’m hoping that the results of the election will show that.”

Most people in Enid will tell you they didn’t hear much about the allegations against Blevins until after he was elected last year.

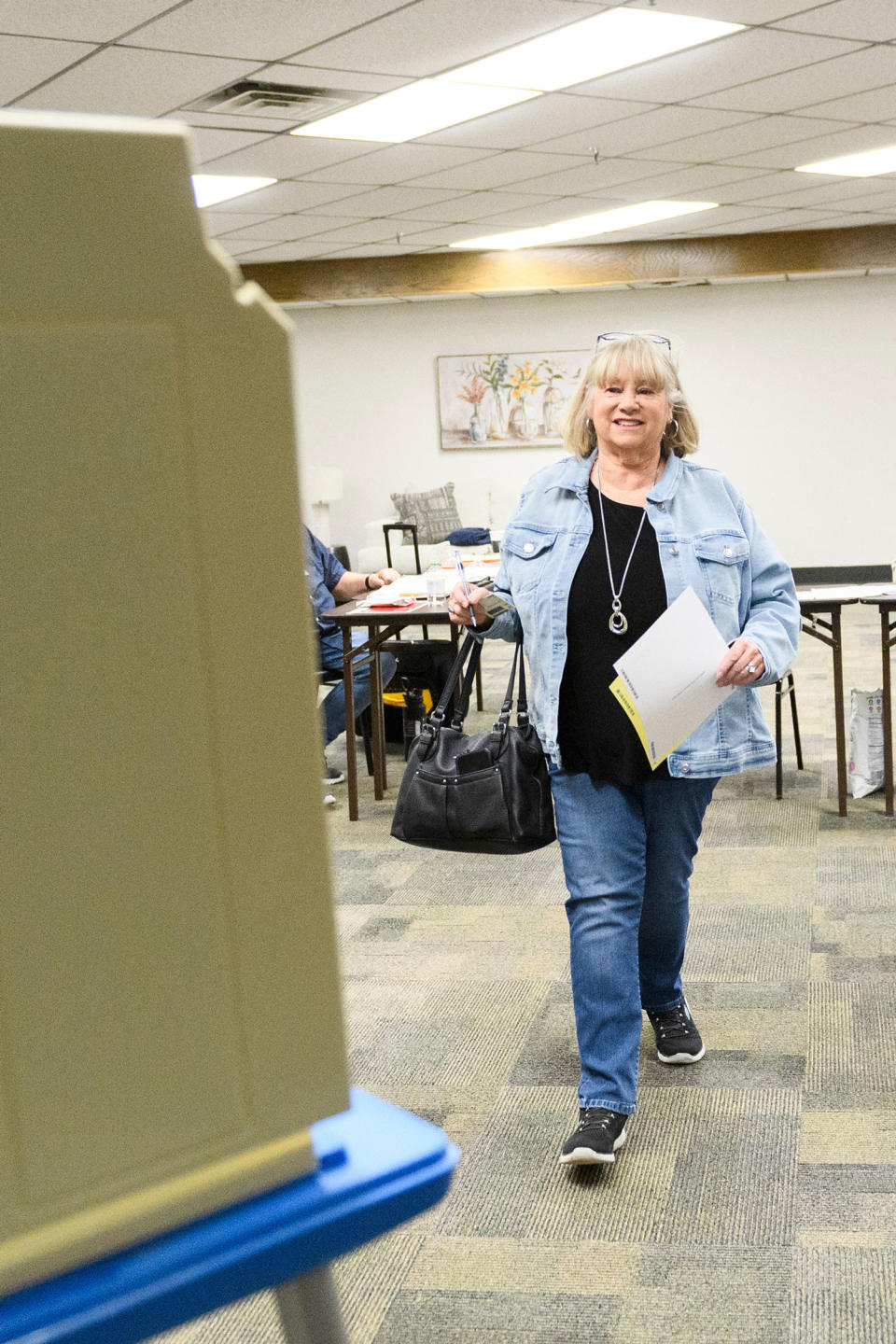

As voters trickled into polling stations Tuesday, many said they didn’t vote in that race and had no idea back then that Blevins, a former Marine who now works for his family’s roofing business, had been active in white nationalist groups. Nearly everyone said they didn’t want their city to be known as a place that tolerates hate.

“It does matter what you’ve done. Who you’ve associated with,” said Paul Martin, a cattle farmer and Democrat who said he votes for candidates regardless of party and learned of Blevins’ white nationalist ties only after his election.

“It didn’t come to light until after the vote,” Martin said. “I was really upset.”

The evidence of Blevins’ activism with white nationalist groups was out there. In 2019, he’d been outed by anti-fascist researchers and the progressive media outlet Right Wing Watch. The articles included photos of Blevins in 2017, marching alongside tiki torch-wielding neo-Nazis at a rally in Charlottesville and the next day at Unite the Right, carrying the original Oklahoma flag at an event where counterprotesters were beaten and a woman was murdered.

They included screenshots of Blevins’ posts: racist and antisemitic writings in secret forums and chats where he identified himself under a pseudonym as the Oklahoma state coordinator for Identity Evropa, one of the largest and most active white nationalist organizations in the alt-right movement. But those articles, which named Blevins as “Judson,” don’t appear when you Google “Judd Blevins,” as he is known in Enid.

The reporting, verified by NBC News, was sound. From 2017 to 2019, Blevins was an active leader in Identity Evropa, a group that privately advocated for the superiority of the white race but sanitized its messaging to break into conservative politics, adopting descriptors like “identitarians” with a mission to preserve “Western culture.” Blevins had flyered cities and universities with Identity Evropa stickers, banners and pamphlets and helped the group grow, recruiting new members and planning activities. He marched in Charlottesville and remained a member for at least a year after. Identity Evropa dissolved in 2019; its leadership splintered to other white nationalist groups.

Using a pseudonym, Blevins posted in 2019 that fellow white nationalists — “our guys” — should be supported as they ran for local elected offices “such as city council.”

“Basically positions where one can fly under the radar yet still be effective,” he posted.

Five weeks before Election Day last year, the local paper, the Enid News & Eagle, published a front-page story: “City candidate accused of white nationalist ties.” Blevins called the article fake news. Moreover, he told supporters, the “George-Soros-funded” left’s attacking him in such a way only bolstered his bona fides as a conservative Republican — a label that he had affixed to his campaign signs and mailers, even though his opponent was also a conservative Republican and the race had always been nonpartisan.

“The labels applied to me are the same applied to any American who speaks out against the ruling liberal establishment,” Blevins told the paper.

Blevins won by 36 votes, and the election shook Enid’s progressive residents. In response, they formed the Enid Social Justice Committee and decided on their first mission: to inform their neighbors of their new council member’s white nationalist ties. In November — after six months of activism, protests and heated speeches at the city’s regular council meetings — when it became clear that Blevins would neither explain nor apologize, the ESJC submitted the signatures it had collected and filed a recall petition.

To recall Blevins required someone else to run against him. In January, Patterson entered the race. She had served on multiple state and local boards and provided a stark contrast to Blevins. Small in stature and soft-spoken, Patterson refused to go negative on the campaign trail.

Meanwhile, Blevins took the gloves off. At a Republican women’s forum, he described Patterson as weak. He told his supporters that she was just a tool of the ESJC and that a vote for her would be a vote for a fringe group of radicals. He compared himself to former President Donald Trump, besieged on all sides by a faction of far-left “perverts” and a deep state within the City Council that went all the way up to the mayor, whom he accused of working with the ESJC and orchestrating Patterson’s candidacy. He doubled down on claims that someone from the ESJC had tried to assassinate him by cutting one of his truck’s brake lines. (Enid police found no evidence to support his allegations.)

Patterson rarely spoke about Blevins in speeches and at fundraisers. She talked about kindness, civility and a return to “normalcy.”

At a public forum last week, though, Patterson was direct. She denied rumors of her recruitment by the ESJC and said she had been asked by local business leaders but was inspired to run by Blevins.

“It was time to step forward,” she said. “It’s time to restore our reputation.”

“I fear that his recent past puts our Air Force base at risk and jeopardizes our ability to recruit businesses to Enid,” she said. Then she went further, referring to a HuffPost report that Blevins’ first campaign had received $1,944 from a Texas man with ties to the white nationalist organization Patriot Front. NBC News confirmed that reporting: Public records showed the donor, who declined to comment, had multiple businesses with a member of Patriot Front, and websites in the donor’s name hosted racist content.

At last week’s forum, Patterson said: “I believe in second chances, but my opponent has not been forthcoming in his continued association with members of the white nationalist movement.” It was a concern shared by members of the City Council and the mayor.

Blevins denied the donations were made to further white nationalism. “It’s not a crime to have a friend who has money,” he said.

In another answer, Blevins denied being a white nationalist but defended having marched in Charlottesville with them. He said he was “opposed to all forms of racial hate and racial discrimination,” then railed against the “anti-white hatred that is so common in media and entertainment.” It was the most Blevins had ever said publicly, by far.

After the candidates left the forum, members of the ESJC and one Blevins supporter, Eddy Reed, lingered outside. For a few minutes they went back and forth, arguing over Blevins and white supremacy as a concept.

“Let me ask you a question,” said Enid Police Chief Bryan Skaggs, who stood between them, arms crossed. “Are either one of you going to change the other one’s mind?”

“Nope,” Reed said.

“So why are we having this conversation?” Skaggs asked. “I’d still like to go home and eat.”

Members of the ESJC met up downtown for a BYOB party Tuesday night at Jezebel’s, a tea house and event space, to watch election results roll in.

Two dozen people milled around, listening to a mix of protest songs that ESJC’s vice chair, James Neal, had made for the occasion. They ate caramel popcorn and cocktail sausages from a slow cooker and drank Irish whiskey and wine and, every few minutes, refreshed the Oklahoma State Election Board’s website on a big screen.

At 8:14 p.m., the webpage showed that Blevins had lost.

“We did it,” Kristi Balden, chair of the ESJC, said to claps and screams.

The lesson, she said, was that a small group anywhere could fight extremism. “You can do this because we did this. We didn’t even know what we were doing, and we did this. This is possible.”

Across town, near Vance Air Force Base, Patterson and her supporters watched the results from her campaign headquarters, a small office space with red and blue table coverings. As supporters cheered early numbers that showed her in the lead, Patterson asked that whatever happened, people not bash her opponent. When the full results came in, they popped sparkling wine.

Enid’s mayor, David Mason, went to the celebration after the regular City Council meeting. Blevins hadn’t attended what would be his final meeting on the City Council; he’d been out campaigning, instead.

Mason told NBC News last month the recall election would either “crater” the city or inspire some much-needed soul-searching.

“I think it’ll rally us, and I think we’ll be better voters because of this,” he said. “It’s easy for me to say we accidentally did this, we didn’t fully understand and, and we’d never do that again. We vote him in a second time? It probably says a lot about who we are.”

On Tuesday night, he gave a toast to Patterson: “I’m so glad you won tonight,” he said, “but more importantly, I think the winner tonight is the city of Enid.”

Now, Enid’s City Council can turn back to other items on its agenda this month: sewer repairs, changes to traffic patterns and six new police cars.

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com