In Black, Latino, Asian and LGBTQ communities, the titles of aunt, auntie, titi or tía are often given to the women who connect us with our roots, serve as confidants or take on a motherly role for those who are grieving or have strained relationships with their own mothers. The labels are often signs of respect and affection, and are not always indicators of a biological connection.

It was Cam McDonnell’s aunt — her mom’s best friend from high school who isn’t biologically related — who stepped up when she first came out as gay. Her mom didn’t take it well, leaving McDonnell, then in high school, to couch surf and stay out of the house as much as possible.

“It really was my aunt who stepped in and said, ‘You gotta just show up for your child,’” McDonnell, who later came out as trans, said. “She has no children, so I think in a lot of ways she looked at me as sort of her godchild, and I think she just was the voice of reason in my mother’s ear.”

The importance of these bonds is now the subject of scientific research. A study published earlier this year reported that aunts hold key roles in supporting young relatives who are LGBTQ, in some cases keeping them from becoming unhoused when their parents are less supportive of their identities. That is particularly the case for Black and Latino LGBTQ people, the study found, adding that extended family members are key parts of Black, Latino and Asian family life.

In acknowledgment of those bonds this Mother’s Day, NBC News asked people across the country to share how having an auntie — or being one — has shaped their lives.

Caitlin Jukes — Dallas

For Caitlin Jukes, 31, being an aunt to two Black nieces and a nephew — Myra, 14, Marcus, 12, and Mia Jukes, 10 — means supporting them through new experiences and giving advice, solicited or not.

Because the children, raised by a single father, James, live in a predominately white Texas neighborhood, auntiehood often includes guiding them through the complexities of racial dynamics, from dealing with microaggressions to doing their hair.

Myra said it is her aunts, Caitlin, Kim and Joyce Jukes, who teach her all she needs to know about caring for her coily hair.

“I don’t know a lot about my hair,” Myra said. “But they’ve experienced the worst and the good in hair, so they know what to do to help it grow. They’re always there to help me.”

Paola Rodríguez — San Juan, Puerto Rico

Paola Rodríguez, 30, said she often finds herself revisiting fun childhood memories of being with her aunts from her father’s side: the sleepovers, the birthday parties, the holidays.

“Those memories and those moments have given me the confidence now as an adult to trust them in situations that are more serious,” Rodríguez said in Spanish. After losing her mother in 2015, these aunts became her go-to when she needs advice and support.

Now she’s preparing to welcome her first goddaughter in June. And like in most Puerto Rican families from the island, a godchild is also a de facto niece or nephew. “She already has me bankrupt, and she hasn’t even been born yet,” Rodríguez said jokingly. “Every time I see anything in a store, I’m like, ‘So cute, for my goddaughter.’”

Zarah Hilliard — Colorado Springs, Colorado

Zarah Hilliard, 24, came out to her parents as a lesbian at 17, and she said they didn’t respond positively at first. So when Hilliard came out to her aunt Wrayanne Wilson, she went into the conversation expecting the worst. But Hilliard said Aunt Wrayanne’s first response was, “OK, so?”

When Hilliard came out to her auntie Sandra “Sissy” Olsen, she said her aunt reminded her that Hilliard’s cousin is gay. “And she was like, ‘I don’t love you any less either, you are perfect the way you are,’” Hilliard said. “I’ll always remember that too. … That was important to me, to just hear that from them, that they didn’t love me any less.”

Hilliard said her aunts’ views had a significant effect on her mom, who became more accepting and supportive.

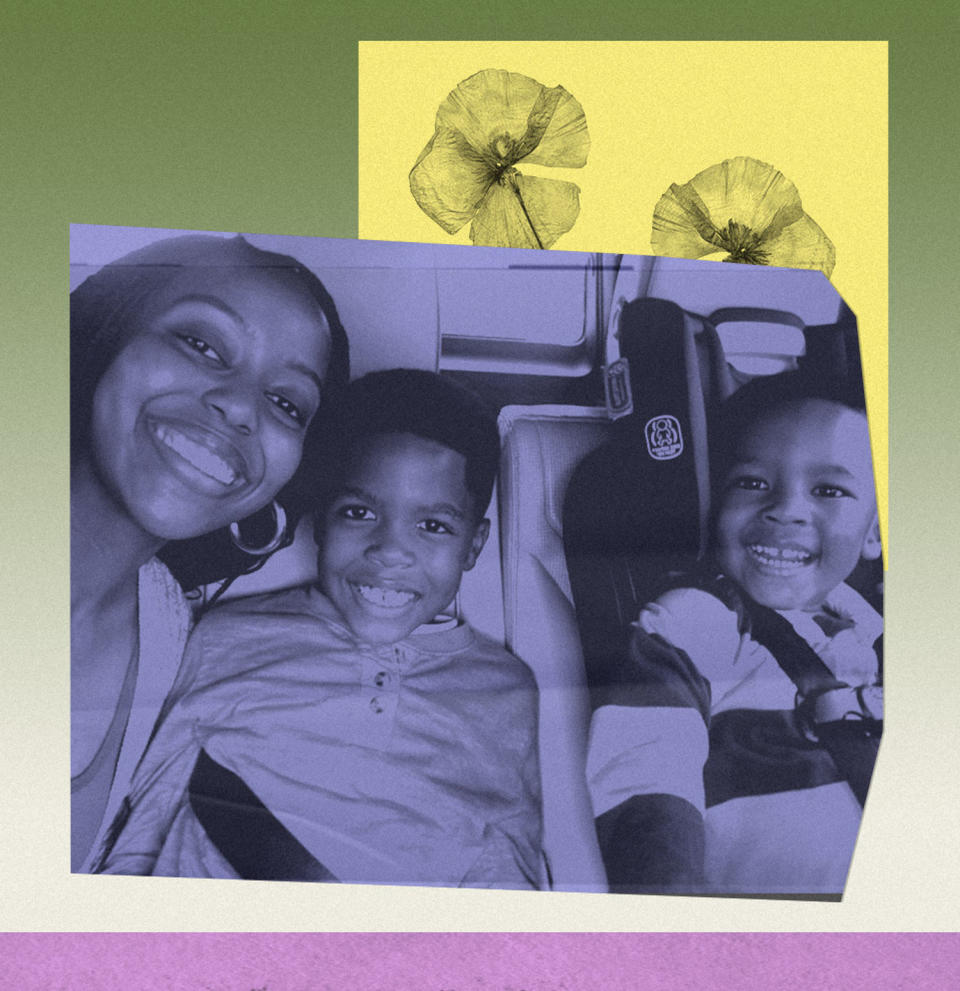

Victoria Shoots — Mobile, Alabama

Victoria Shoots, 34, says the aunt-nephew bond is magical. As the only aunt to Logan, 8, and Andrew, 4, they call her “one-tie” instead of auntie.

“I’m in their lives to teach them things that maybe their parents haven’t gotten around to, or culturally relevant things their parents may not be into that I think are important for them as Black boys to know and understand,” Shoots said.

“I always want them to know this is a safe space outside of their parents. I’m their secondary safe space,” she said. “The world is already going to try to silence them, but we don’t want to do that. We want to raise whole and free children.”

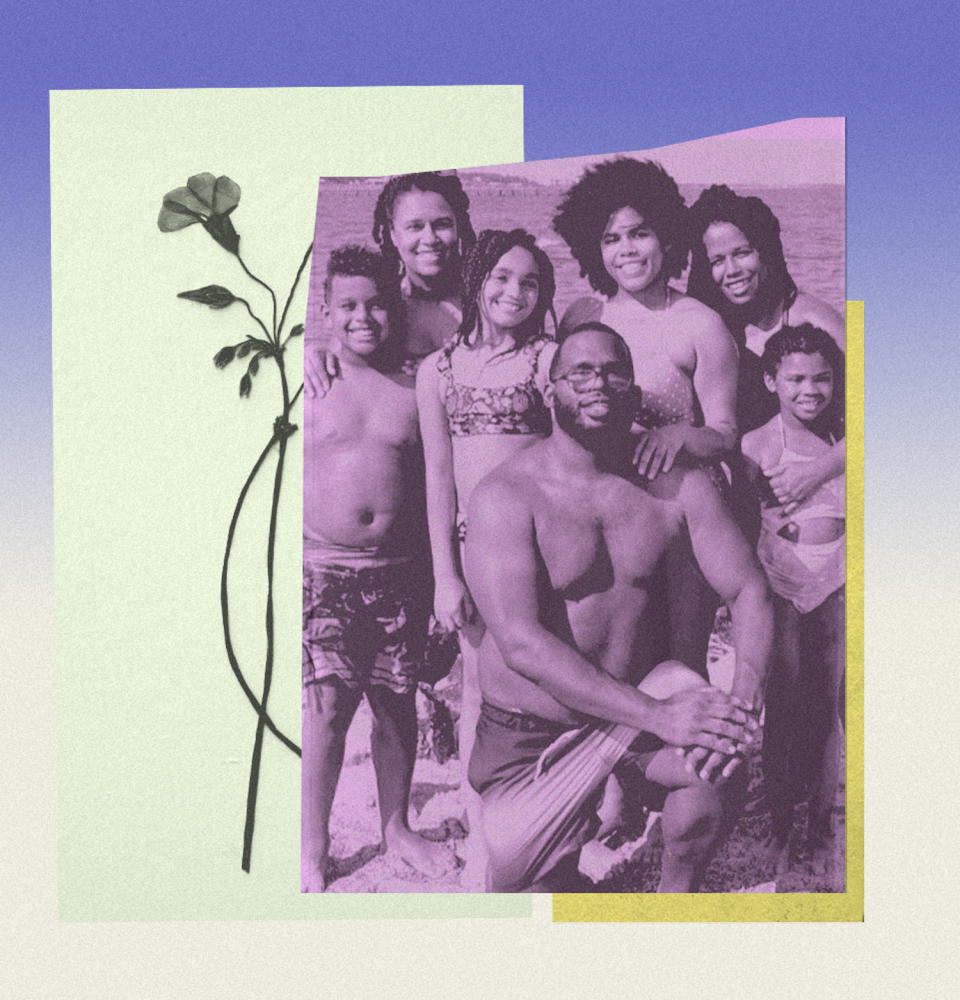

Jacqueline San Nicolás — East Los Angeles, California

In 2019, Jacqueline San Nicolás, 29, returned to her hometown of Los Angeles from the East Coast. “One of the biggest reasons for moving back to California was to be with my niece and nephews,” she said.

At the time, her three nephews and her niece, ages 12, 9, 8, 7, were grappling with their adopted parents’ separation and a pandemic. San Nicolás moved in with them. “I got to be some sort of stability for them,” she said.

From being present at their school functions to explaining to her young niece the importance of wearing a face mask even though it would sometimes make her eyeglasses fog, the experience helped create “a very intense level of bonding” between her and her niece and nephews.

Since moving out in 2022, San Nicolás has established new traditions with them to continue nurturing their bond. She takes them out to eat every time she returns from a trip, “and boy, do they hold me to it!” San Nicolás said, laughing.

Prisca Choe — Philadelphia

Prisca Choe, 31, says aunties in her life have functioned as both pillars of the community and as personally impactful, safe spaces to turn to. For her, one of the most significant examples is her nonbiological auntie Winnie Mui, with whom she doesn’t share a language.

Choe, who is Korean American and lived in New York City’s Chinatown for six years, would frequent Mui’s popular karaoke bar Winnie’s and often spoke to her auntie through a friend who’d play translator. Though the language barrier would at times prove challenging, Choe said, Mui still provides the comfort of a “stable shared space.”

“We can just vent about things and it’s not always about that other person needs to understand, but they’re sitting there, still listening to you talk,” Choe said. “It means so much more if they care to hold that space even when they don’t understand what you’re saying.”

Mui, a beloved fixture in Chinatown, also plays a vital role in her community, Choe added, as many aunties do. “Uncles kind of float around and they can be fun. But the people who actually build the space and organize the way that we come together have always been aunties,” she said.

Jyoti Mandavia — Queens, New York City

Jyoti Mandavia, 72, said she takes her role as an auntie seriously, providing both fun and encouragement to her own grandchildren, as well as her nephew’s kids. Mandavia explained that throughout the years, she’s taken on babysitting duties and loves making them snacks and Indian curries to give them a taste of home. But the emotional care she provides is perhaps the most critical part of her role as an auntie.

“Young kids, teenage kids have problems with parents all the time,” Mandavia said. “So [my nephew’s daughter] will come to my door and knock on my door and say, ‘Auntie, I need your help.’ And we talk about things and then I calm her down. … When I see the parents I said, ‘Can you meet your daughter halfway?’”

Mandavia, whose husband died when she was young, said her empathetic style of auntie-ing has paid off. Often, those she helped care for will check in on her and return the care that she’s given them, she said.

“The emotional support I get … makes me feel so good that somebody is there,” she said. “It is a privilege to be an auntie.”

Roselyn Dana — Phoenix

Carmen Santini is the quintessential matriarch in her family. As one of 12 siblings, Santini has dozens of nieces and nephews and knows their birth order and their birth dates. Despite never having had children of her own, Titi Carmen, as many of her nieces and nephews call her, is viewed as the ultimate caretaker by her “sobrinos.”

Santini, now 78, moved to Brooklyn from Puerto Rico in 1970 to work as a registered nurse at a veteran’s hospital. She first moved in with her sister and her niece Roselyn Dana, now 54.

“She’s like a second mother,” Dana said. Her aunt, whom she moved in with when she was 15, was her confidant and often the strict figure she needed at times, she said. “Now as an adult looking back, I wasn’t easy. I wouldn’t be where I am today without my aunt.”

Alyssa Yeh — Los Angeles

Alyssa Yeh, 23, whose family was active in the Chinese American Christian community, said most of the women she describes as “aunties” are from the Southern California church she grew up in. They served as an extension of her mother, helping to look after her when her parents were busy. At times, they’d spoil her too.

“Both my parents worked, so they were always arranging car pools or just someone to watch me, so Auntie Janet would come pick me up from school. Someone else would take me home from church choir and buy me ice cream on the way home,” Yeh said. “There were always women in my life to step in and take care of me.”

While Yeh said aunties wouldn’t necessarily exert the same kind of authority over her that her parents did, she would sometimes feel overly surveilled by them, especially when she got older.

“It was definitely a huge source of anxiety for me, growing up feeling spotlighted, especially in church,” Yeh said. “I think thorns come up sometimes when I think about certain comments. But overall, I think I have an appreciation for this network of volunteers who raised me.”

Aaron Buday — Raleigh, North Carolina

Aaron Buday, 29, said he called his aunt Cindi LeMon’s visits “spoil fest” when he was growing up. She would bring arts and crafts for him and his cousin, and she would never give Buday, who later came out as transgender, girly items.

When Buday was 16, he came out as trans to his parents in a letter, which he said was not well received at the time. He then came out to Aunt Cindi, and one of her first responses was, “OK, you’re my nephew. I love you,” said Buday, who uses he and they pronouns.

He said his parents needed a therapist to explain his gender identity to them, but Aunt Cindi didn’t need that. “She was just ready to go, feet on the ground, like, ‘Yep, that’s who you are,’” they said. Buday also has a fond memory of her texting him because she was updating his contact in her phone to his new chosen name, and she wanted to make sure she spelled it correctly.

Adrián Valle Torres — Jersey City, New Jersey

Hoping for a better paying job in advertising and an opportunity to dip his toes into acting, Adrián Valle Torres, 33, decided to try his luck in New York City several months after Hurricane Maria hit his native Puerto Rico in 2017.

Even though he didn’t grow up having a close relationship with his great-aunt Debbie Pérez, whom Valle Torres calls Tía Debbie or Aunt Debs, she opened the doors of her New Jersey home to him when she learned of his aspirations.

“They took a chance on me and I’m very thankful forever to them,” Valle Torres said, adding that he tries to meet with her every Sunday for dinner. “I’m building my life in America thanks to them,” he said of his aunt and uncle Reinaldo Pérez.

As Valle Torres, who has already appeared in some films and TV shows, continues to build his life in the States, one of his “adopted aunts,” Titi Vane, has also been a crucial support system. “She’s literally my compass when I feel lost,” Valle Torres said in Spanish.

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com