Our Uniquely Fort Worth stories celebrate what we love most about Cowtown, its history & culture. Story suggestion? Editors@star-telegram.com.

The muddy Trinity River by any other name would still be muddled in history.

Efforts to revive the river’s Native American name led some advocates of Indigenous rights to announce in 2018 that the river meandering from North Texas to Galveston Bay was initially called the Arkikosa. The word was supposedly a Caddo term meaning a river so clean and pure, it was a perfect “place to wash your face” — an ironic twist on later epithets deriding the water quality. D Magazine’s arts editor embraced the term and advocated revising local maps.

Four years later in 2022, language preservationists from the Caddo Nation determined their ancestral language lacked the letter “R” sound. Arkikosa was likely a corruption or misspelling of the word Akokisa. In the vernacular of another tribe, the Atakapa who settled in the Gulf Coast woodlands, Akokisa means “river people.”

“This is where things get complicated,” says Annette Anderson, who serves on TCU’s Native American Advisory Circle and the council for the Indigenous Institute of the Americas, a Plano-based nonprofit.

“One article gets it wrong or has not been updated, and it gets quoted over and over on the internet,” Anderson said. “The Caddo Nation has a language department in Oklahoma that will be happy to validate that for you. The river has always been sacred to native people since before time was recorded. Each nation had a language and a unique view for referencing the river. Our histories are very complicated.”

Research continues not only into the river’s indigenous names but into its environs. In downtown Fort Worth, at the confluence of the Trinity’s West Fork and Clear Fork, naturalists have documented 57 species of butterflies and moths, 24 kinds of fish, 23 species of dragonflies and damsel flies, 49 species of birds, and 35 types of ants, wasps and bees.

Each of these, plus 109 native plants, are posted at iNaturalist.org, thanks to biologist Andrew Brinker, a Tarrant County College adjunct professor and Fort Worth ISD science teacher. With high school biology students and a grant from TCU, he also documented seven species of turtles from soft shells to snappers and sliders.

Throughout the Trinity River’s recorded history, the waterway has been called many names — most often insulting epithets such as the Big Ditch. During the past five decades, there has been a gradual turnaround. A river once deemed “septic” by the U.S. Public Health Service now has a 120-mile paddling trail, 21 canoe launches, outdoor festivals and Independence Day fireworks. In 2020, it was designated a National Recreation Trail by the National Park Service.

Dating back to European colonization, French explorer La Salle in 1687 named the waterway the “River of Canoes.” Three years later, Spanish explorer Alonso de Leon christened it “La Santisma Trinidad,” the “Most Holy Trinity.” He was convinced that self-sufficient natives living in the watershed’s forests were ripe for Catholic missionizing.

In contemporary times, secular souls often assume the river was named for the three forks that converge into the main trunk of the Trinity — the Elm Fork, Clear Fork and West Fork. That’s mere coincidence, because de Leon never reached this far north and was likely unaware of the three forks. Paddling guides call the region Three Forks Country, says Charles Allen, owner of Oak Cliff’s Trinity River Expeditions.

In the 1920s, the Trinity was infamously dubbed a “River of Death,” because the Swift and Armour slaughterhouses in the Fort Worth Stockyards dumped beef carcasses and blood into Marine Creek, a Trinity tributary.

Other tributaries were undisturbed. Oilman Tex Moncrief remembered skinny-dipping at a swimming hole on the West Fork. Artists Stuart and Scott Gentling hunted with bows and arrows for herons, egrets and woodland ducks — an illegal pastime. The brothers painted detailed pictures, a la Audubon, for their 1986 book “Of Birds and Texas,” a collector’s item.

From Dallas’ earliest days, politicians tried to extract profit from the river by transforming it into a shipping canal with locks and deep, straight channels. Repeatedly, deadly floods washed out the dream of turning Big D into a lucrative port. Among the worst floods was the deluge of 1908 that swept outhouses, sheds, livestock and railroad trestles downstream.

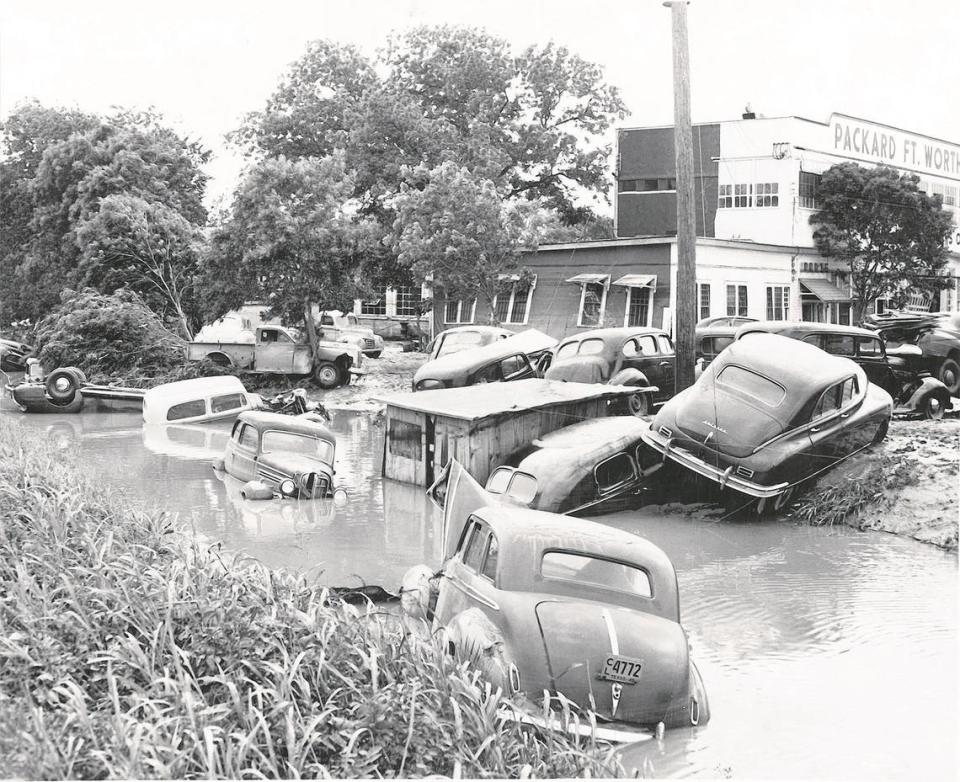

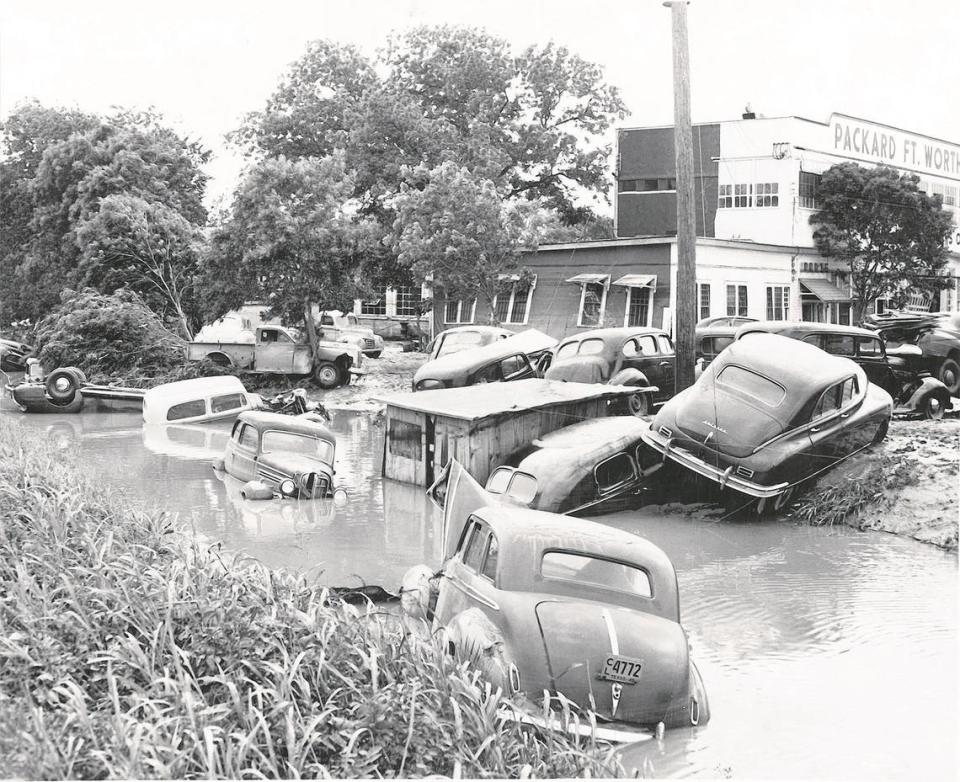

In Fort Worth, the most destructive flood on record was May 16-17, 1949. In its wake, 13,000 people were left homeless. One-tenth of the city was underwater. Horses stood stranded on rooftops. Ten people perished. The high-water mark rose to the second floor of Montgomery Ward on West Seventh Street, today’s Montgomery Plaza.

The Army Corps of Engineers responded by straightening and channelizing the Trinity, cutting down trees, and raising levees to contain future floods. The city turned its back on the river, ignoring litter and laughing at the designation “Big Ditch.” During years of drought in the 1950s, the river did not flow. There were only stagnant pools.

In 1969, the dynamic Phyllis Tilley organized a Trinity River bus tour for Junior League volunteers, civic leaders and elected officials.

“We’ve got to clean this up,” declared Tilley, in whose memory the Phyllis J. Tilley Pedestrian Bridge was constructed in 2012.

Her efforts led to the creation of Streams and Valleys Inc., a nonprofit that works with Fort Worth Parks & Recreation and other partners to beautify the river, develop recreational amenities and plan low-water dams.

In 1971, there were three miles of trails along the river, mainly for maintenance vehicles. These days, hikers, bikers, joggers, rollerbladers, pedestrians, horseback riders and drivers steering scooters and Segways enjoy 72 miles of trails. Life along the river thrives, no matter what it’s called, how it’s spelled, or what its name implies.

Author and archivist Hollace Ava Weiner has had a season’s rental pass at TC Paddlesports at Panther Island since 2021.