Al Massira Dam, which sits around halfway between Casablanca and Marrakesh, contains just 3% of the average amount of water that was there nine years ago, figures show.

Six consecutive years of drought and climate change, which causes record temperatures that lead to more evaporation, have threatened water supplies across the North African nation and hit agriculture and the economy in general.

The satellite images that the BBC looked at were taken in the same month, March, over successive years from 2018 to 2024.

They show a stark transformation in the landscape, with areas that are normally green becoming parched and beige.

The images also “clearly depict a rapid change in the reservoir’s surface area”, Prof Brian Thomas, a hydrogeologist who has analysed satellite images for Nasa, said.

The appearance of the water had also changed, he added, indicating shifts in land use and the flow of the river feeding the reservoir.

But the impact of the drought is not confined to the area around Al Massira – it stretches across the country.

Agriculture accounts for just under 90% of water consumption in Morocco, according to World Bank data from 2020, and farmers have been suffering.

Abdelmajid El Wardi cultivates cotton and wheat, as well as rearing sheep and goats, on his land to the east of Ain Aouda, near the capital, Rabat.

But he has reaped little in recent years.

“The most difficult drought we have experienced in history is this year,” Mr Wardi said.

“For me, the current agricultural year is lost.”

His ewes had stillbirths because of the lack of water and food available to sheep during the drought.

Even the nearby wells fed by groundwater had little left in them, he said.

A short drive to a nearby valley and the broader issue becomes visible as a river clearly affected by the drought comes into view.

Mr Wardi said he thought that around just 30% of another reservoir sitting behind the Sidi Mohammed bin Abdullah dam – located further upstream – remained.

The farmer has been forced to sell sheep and turn to agricultural loans in an effort to support himself and his family. He said the state had provided some help but it was not enough.

Hammams closed

Recent rainfall has led to a short-term respite, but ultimately, it is nowhere near sufficient to counter the consecutive years of drought.

Aside from the impact on agriculture, the shortage has also affected the country’s famous hammams – or public steam rooms and saunas – which have been ordered to close for three days a week to save water in key cities.

The authorities have launched a national campaign in an effort to encourage people to conserve more water.

In January, King Mohammed VI chaired a meeting looking at the water situation across the country where Water Minister Nizar Baraka said there had been an alarming 70% drop in rainfall between September 2023 and mid-January compared to the average.

The king urged the ministers to redouble efforts to ensure a supply of drinking water to all regions, according to a royal palace statement.

To help ease the situation, the country is investing more in seawater desalination plants. But these facilities require a high amount of energy and can eject concentrated salt water and toxic chemicals back into the sea and ocean that are harmful to the environment.

Al Massira has been particularly badly hit by a lack of rainfall and the changing climate, according to the water ministry.

It had continued to supply water to cities such as Casablanca and Marrakesh, the country’s tourist capital, but its use for irrigation by farms had been suspended since 2021, the water ministry told the BBC.

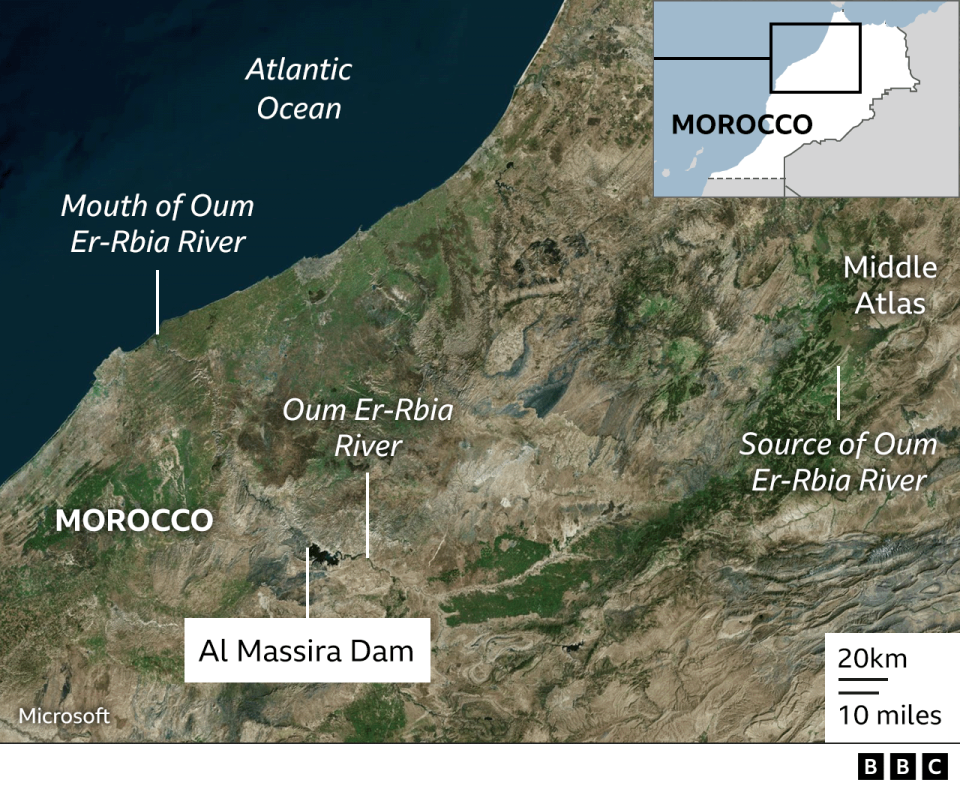

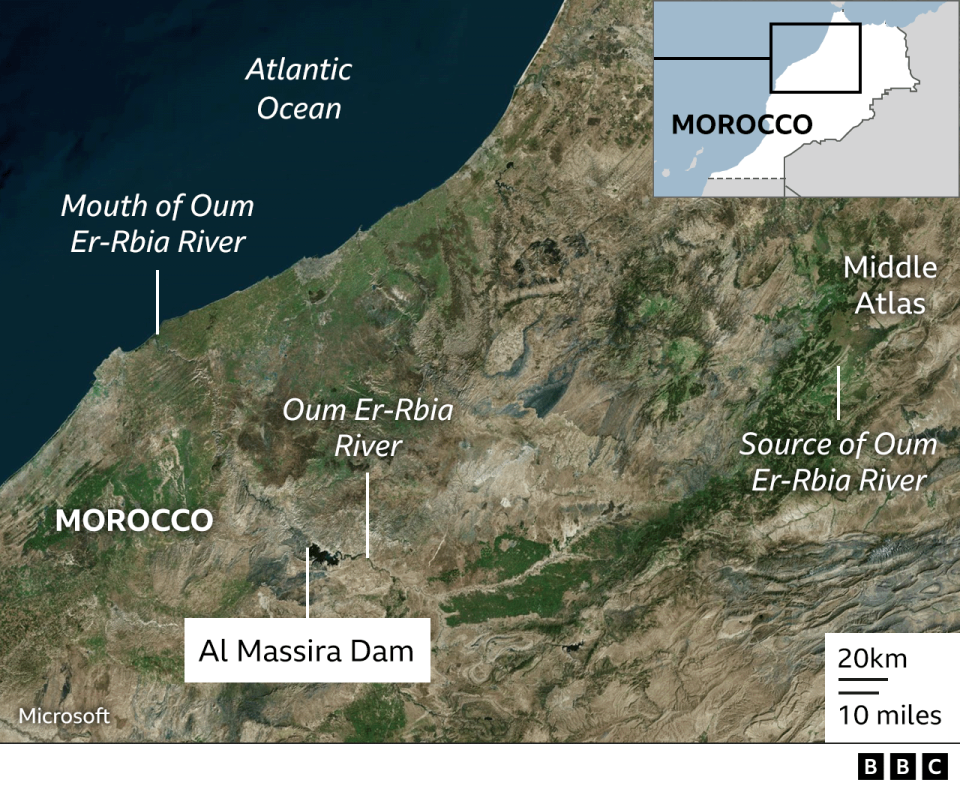

The reservoir lies on the Oum Er-Rbia River, the second longest in Morocco, which has experienced a significant reduction in inflow that can be traced back to its source in the Middle Atlas mountains.

Prof Abdelfattah Benkaddour, an expert from Marrakesh’s Cadi Ayyad University, said that all of the water resources flowing into the river were “shrinking” and many springs that feed it had disappeared.

The higher areas in the mountain range had also not seen the usual snowfall which, when melted, supplied the river, environmental analyst Prof Abba El Hassan told the BBC.

The situation has been exacerbated by evaporation which increases as the heat rises. Last year, Morocco recorded its highest-ever temperature of 50.4C on 11 August.

All this added together meant that the fresh water systems in Morocco were “crossing thresholds” that records had never seen before, Dr William Fletcher, a geographer at the UK’s Manchester University, said.

His research has shown how sensitive Morocco is to climate change. Pollen records indicate that the Atlas cedar trees, that have survived in Morocco since “at least the last ice age”, are now at risk of local extinction, Dr Fletcher has found.

He said long-term projections mean that Morocco will have to continue to adapt to more frequent droughts.

“It’s important to recognise that there have always been droughts in Morocco throughout history, but global climate change is increasing the frequency and intensity of droughts… and that will continue through this century.”