Timber smuggling, estimated to be worth $23m (£18m) a year, from Mozambique’s ancient forests into China is helping to fund a brutal Islamist insurgency as well as a large criminal network in the north of the Southern African country.

This illicit trade in rosewood is linked to the financing of Mozambique’s violent militants with links to Islamic State in the northernmost province of Cabo Delgado, according to data seen by the BBC from the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), an NGO that campaigns against alleged environmental crime.

Rosewood is a catch-all trade term for a wide range of tropical hardwoods that are highly prized for luxury furniture in China.

Mozambique’s rosewood is protected under an international treaty, meaning only very limited trade that does not threaten the species is allowed.

However, a four-year undercover investigation by the EIA in both countries has revealed that poor management of officially sanctioned forest concessions, illegal logging and corruption among port officials is allowing the trade to expand unchecked in insurgent controlled areas.

The revelation comes at the same time as a significant resurgence in fighting in the north of Mozambique. On Friday, at least 100 insurgents staged their boldest attack in three years on the town of Macomia, which was eventually stopped by the army.

The location of the attack confirms that the insurgency has moved its bases further south due to the increased presence of soldiers in the north. It “has also gained enough funds to recruit in neighbouring Nampula province further south”, according to Mozambique analyst Joe Hanlon.

A Mozambique government report published earlier this year and seen by the BBC – the National Risk Assessment on Terrorism Finance Report – says al-Shebab insurgents have taken advantage of the illicit timber trade to “fuel and finance the reproduction of violence”.

The report says the insurgents’ involvement in the “smuggling of fauna and flora products”, including wood, and the “exploitation of forest and wildlife resources” is contributing to a “very high level of fundraising” for the insurgency group. It estimated its revenue from these activities amounted to $1.9m a month.

Given the challenge in accessing the Cabo Delgado region it is hard to quantify the insurgents’ level of day-to-day involvement in the timber trade but there have been reports of firms paying a 10% protection fee to insurgent groups to carry out illegal logging in forest areas.

Forests with valuable trees – not just rosewood – are divided up in to chunks, or concessions. Anyone who wants to log these areas must pay a fee to the authorities. These are typically licensed to a Mozambican national – the middleman – and rented out to Chinese logging firms.

Trading sources who did not want to be named estimate that 30% of the timber logged in Cabo Delgado is at high risk of coming from insurgency-occupied forests.

There are thought to be three main forested areas in Cabo Delgado where logging and timber sales take place: Nairoto; Muidumbe and Mueda, plus one more in Napai, in neighbouring Nampula province.

While the Chinese authorities have made it illegal to log rosewood in their own country, huge quantities continue to be imported.

Rosewood is given a customs code for hongmu (meaning red wood in Chinese) on arrival in the country, which allows researchers to trace it.

Mozambique was China’s top African supplier of hongmu wood last year, providing over 20,000 tonnes worth $11.7m, according to Trade Data Monitor, a commercial company that tracks global trade.

It has overtaken other countries like Senegal, Nigeria and Madagascar as their rosewood species have been stripped or depleted, or laws banning exports have been more strictly enforced.

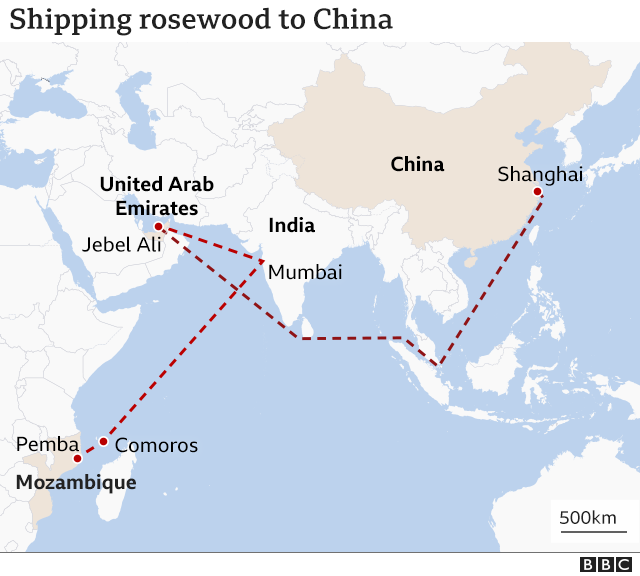

As part of its undercover investigation, the EIA tracked a huge rosewood shipment out of Mozambique.

Between October 2023 and March 2024, investigators traced around 300 containers of a type of rosewood known as pau preto from the port of Beira to China.

Pau preto rosewood, which is found in the north of Mozambique and in Tanzania, is classed as a threatened species on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) red list.

These 300 containers were transporting 10,000 tonnes of the rosewood. Trader estimates value each container at around $60,000, putting the value of the total shipment at around $18m.

EIA undercover footage seen by the BBC shows some of this specific shipment was also in raw log form – rather than planks that had been processed through sawmills. This breaks Mozambique’s own 2017 law on exporting any unprocessed timber.

The containers also held processed planks.

Industry sources say that typically when trees are cut down by loggers in Cabo Delgado’s forests – either at concessions operated largely by Chinese firms, or illegally beyond these boundaries – the timber is taken to be processed at sawmills around Montepuez, a large town in Cabo Delgado.

This timber from multiple sources is then mixed up and moved from the Montepuez mills by trucks to the ports of Pemba or Beira.

At these ports the cargo should be inspected by Mozambican authorities and receive a permit or export licence. But the EIA says the logs are often mis-reported or not declared at all in customs paperwork.

Rosewood transported between Mozambique and China is carried by two of the world’s biggest global shipping lines, Maersk and CMA-CGM, according to the EIA investigation.

A spokesperson from Maersk said in a statement to the BBC that it is “committed to combatting illegal wildlife trade and will not knowingly accept bookings of wildlife or wildlife products, where such trade is contrary to CITES or otherwise illegal. We request our customers to correctly declare the content of their cargo and we are dependent on customs authorities to verify the declarations and certificates. Shipments can only take place against CITES certificates and authority approval.”

The statement explained that it is common in shipping for customers to load and seal their containers before handing them over to the shipping line.

A CMA-CGM spokesperson said it transports goods belonging to customers compliant with local and international regulations and is “not responsible and has no way to control the origin of the goods which are all shipped into sealed containers”.

The spokesperson also said that “CMA-CGM does not transport unprocessed wood anymore, and has introduced a rule forbidding the reservation of space on board the group’s vessels for unprocessed wood leaving Mozambique”.

Deforestation in Mozambique is continuing apace. The country is losing the equivalent of around 1,000 football pitches of forest cover every day, according to NGO Global Forest Watch.

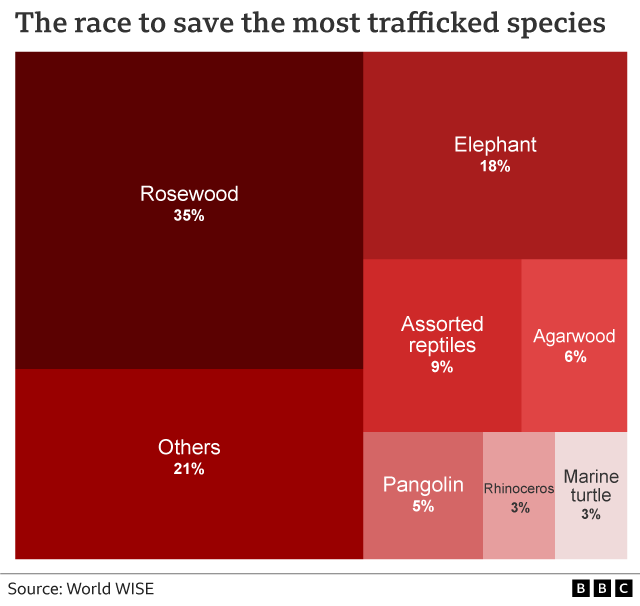

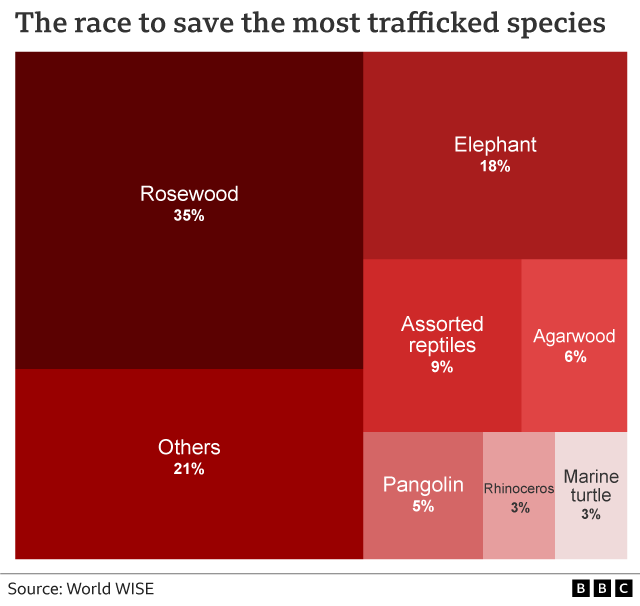

The trade of rosewood is supposed to be restricted under Cites, yet it has become the most trafficked wildlife product in the world, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. In terms of value, it now far out paces trade in elephant ivory and rhino horn.

Pau preto rosewood is listed on Cites Appendix II, for it to be exported legally the Mozambique government must complete a thorough scientific investigation called a non-detriment funding study (NDF) to ensure trade does not threaten its survival.

The BBC asked the Mozambican representative to Cites Cornelio Miguel, who works for the National Administration of Conservation Areas, if an NDF on pau preto had ever been carried out. He did not provide a comment.

Without this assessment, any trade violates the international treaty. China, as a signatory, would be breaking the treaty’s terms in accepting non-compliant imports.

The BBC contacted some of the Chinese trading firms cited in the EIA report, but none were willing to comment on whether they were being supplied with timber from Mozambique.

For environmentalists like Dr Annah Lake Zhu from Wageningen University, this treaty can only ever be as robust as the governments enforcing it. She believes sustainable management of the rosewood trade needs a total rethink.

Dr Zhu says the treaty does not halt the insatiable demand from China’s elite for hongmu furniture.

She suggests the process of listing specific species before they are more tightly regulated may even be driving market dynamics as it “effectively advertises upcoming shortages” and in turn, creating scarcity.

Strengthening the law and bringing in a more sophisticated tracing system would improve the situation. But in practice, conserving rosewood can only work if source countries and timber dealers make it a priority.

In conflict zones such as Cabo Delgado this looks unlikely to happen.

In many ways Cabo Delgado is the “perfect place” for an illicit timber trade to blossom, says EIA Africa programme manager Raphael Edou. He describes the province as a nexus of trade routes, with a mix of lawlessness, corruption, and a desperately poor local population.

Aside from being home to some of the world’s most valuable trees, Cabo Delgado has other lucrative sources of wealth within its borders, including oil, natural gas, rubies, and sapphires.

These treasures pull in huge global investors such as the French energy firm, Total, which has built a $20bn gas liquification plant.

Fabergé jewellery brand owner, Gemfields Group, owns 75% of the Montepuez ruby mine in Cabo Delgado. In 2023, its revenue was $167m.

Insurgent activity in the province has led to one of Africa’s most significant displacement crises, with more than a million people forced to leave their homes.

The insurgents target civilians, carrying out massacres, beheadings, rapes and kidnappings. Houses and whole villages have been bombed and burned.

The violence has destabilised most of Cabo Delgado for almost a decade prompting the government to rely on foreign troops to police the province.

The authorities are struggling to reinforce laws designed to protect Cabo Delgado’s most vulnerable people, let alone those designed to protect its environment and forests.