“I would tell you, from my perspective,” Sherman said to a small audience, “this election is about hope.”

It was.

At one time.

But a city big on hope rejected Tuesday a campaign built not on a grand future, but one that more recently embraced fear. In a landslide, Jackson County voters said no to Question 1, a proposal to extend a 3/8th-cent sales tax to help fund the stadiums.

The final tally: 58% no, 42% yes.

In the coming days, weeks and perhaps even months, you’ll hear that Jackson County rebuffed downtown baseball, or rebuffed the Chiefs’ and Royals’ respective futures within the county’s boundaries.

Don’t buy it.

The voters of Jackson County did not reject simply the concept of sending taxes to billionaires to fund shiny new objects. This is not a cozy fit into a national narrative. They rejected a haphazard, moving target of a campaign that asked voters to trust what would come after the vote rather than what had come before it.

In fact, this mess of a campaign, the Royals’ 16-month crusade for a sweeping change in particular, could be defined in two words: Trust us.

In the absence of transparency, however, comes the absence of trust.

The rebuke is not about something the majority of those in Jackson County don’t want. They’ve been quite comfortable with public money invested in stadiums for a half-century. This is about what they do want. About what they deserve. About what’s missing.

The fine print.

The full scope of the project.

And you bet they’re entitled to it.

That refers to one of the projects especially. The Royals initially promoted their proposal for a move downtown as a transformative change. But they offered only vague assurances about what that transformation might entail, whom it might affect or how it might affect them.

Details, they said as recently as last week, were to be determined after Election Day.

How could that be? That’s the root of the public repudiation.

Kansas City, a town full of civic pride intertwined with these two teams, a town that defines the phrase fear of missing out — and a town that brags about its growth — is the town that just turned up its collective nose at a sales tax. And that’s even after it was told that would be the only way to keep its hometown teams.

There are jokes about how willing Jackson County voters are to support new taxes. They just shook their heads at the things they hold most dear, consequences be damned.

That should be a message. When you don’t show your hand, people are rightfully inclined to question the cards you’re holding. That is not the fault of Jackson County, but rather mostly a Royals project whose plot became more difficult to follow than “Inception.”

The Royals spent considerable energy telling us they were flirting with a new relationship in North Kansas City and Clay County, only to turn around and request renewal of their current relationship with Jackson County for another four decades — and then they, along with the Chiefs, threatened to leave for good if they weren’t accepted back with open arms.

Quite presumptuous.

They narrowed the location of their ballpark to two finalists, only to six months later announce another selection altogether, one that put them under a time crunch for details they could not deliver. And unlike the many self-imposed deadlines that came and went, they could not push this one back.

They then tweaked that final location, the one in the East Crossroads at the site of the former Kansas City Star press pavilion. That happened all of six days ago, when they agreed to keep Oak Street open and meet a request that Mayor Quinton Lucas had made several weeks earlier.

Some within the campaign complained about what they termed misinformation, a hot-button term befitting the conservative group that became heavily involved in the teams’ campaign. But this is an unequivocal fact: Among the many 11th-hour aspects of this ballot initiative, the teams were able to secure a public endorsement from Lucas only 72 hours before the polls opened.

The Royals’ and Chiefs’ proposals were set to affect more than 700,000 people in some form, and they would have affected some in a larger way. Yet, had Tuesday’s measure passed, a contingent of business owners in the Crossroads District would have woken up Wednesday morning uncertain of their future — both inside what the project is calling its “demolition zone” and on its perimeter.

The Royals had promised to be “good neighbors,” another catchphrase that came without an answer to a key question: How?

Or, rather: How exactly?

Less than week ago, even after agreeing to keep Oak Street open, Sherman acknowledged he didn’t know what that meant for a surrounding entertainment district that he said the team isn’t really calling an entertainment district anymore. We still don’t have those details.

Even those inclined to be trusting — I’ve maintained this was more about strategical errors than bad faith — were left without a consistent message or reasoning to latch onto. And they faced a vocal opposition, rooted in community groups consistent in messaging for years. That’s another lesson.

In the end, voters were asked to chew on mystery meat. And instead they spit it back where it came from and said, Try that again.

Will they? I know you’re wondering about the full weight of the consequences that await now, the futures of the Chiefs and Royals in Jackson County — or whether they’ll ever again attempt a joint ballot measure.

I have some thoughts that will be more fully developed over the coming days, weeks and months. It will be an absorbing chain of events to follow, with more moving parts than a Royals proposal for a downtown ballpark.

There are more than a few who believe an offer from Kansas is waiting, that Gov. Laura Kelly wouldn’t exactly be starting from scratch a plan to lure the Chiefs. We’ll see. There is less certainty with a Royals organization that just tried to sell the public on moving into the city, not another suburb away from it.

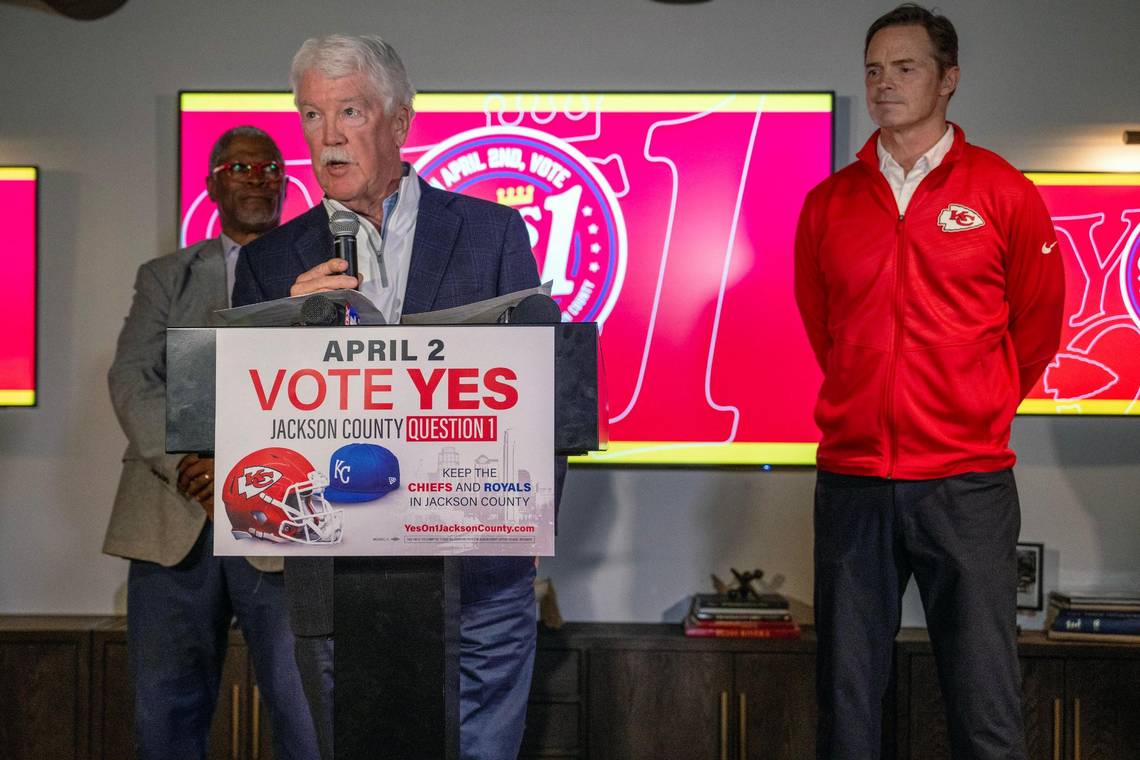

They were asked that question late Tuesday. As Sherman and Chiefs team president Mark Donovan departed the stage at a muted J. Rieger & Co., at the hour in which they’d hoped to be celebrating in the West Bottoms, they ignored a question about the future of their teams in Jackson County as though they didn’t hear it.

What we cannot ignore, however, are the reverberations of what Jackson County voters delivered in the present.