When Laura Kowal decided to date again after losing her husband of 24 years, the 57-year-old retired hospital executive from Galena, Illinois, joined an online dating site because that felt safer.

The relationship she forged with a self-described Swedish investment adviser named Frank Borg began with florid emails and giddy phone calls in October 2018. It was romantic and exciting — but it soon became more furtive.

On August 7, 2020, Kowal’s daughter, Kelly Gowe, received a voicemail from a federal investigator informing her that her mother “may have been involved in a fraud scam” as a victim.

The events that followed not only ended in tragedy for Kowal, they would transform the life of her daughter. Gowe still grapples with all that transpired after receiving that phone call, but she has launched herself at a new cause: to demystify romance scams, a crime that has victimized tens of thousands, many too ashamed to report it.

“It wasn’t until I learned that I was going to have a daughter of my own that I knew that one day she would know the full story,” Gowe told CBS News. “But I want her to know that her grandmother’s story has the ability to educate people and to promote change, and ultimately her grandmother’s story can save someone’s life.”

Family photo

“Anybody could be a victim”

Kowal’s story is not unique. More than 64,000 Americans were defrauded out of over $1.14 billion by romance scammers last year, according to the Federal Trade Commission — a figure experts say likely vastly underestimates the amount of damage done.

Deputy Assistant Attorney General Arun Rao, who oversees the Consumer Protection branch of the Department of Justice, said one of the biggest challenges facing law enforcement is how few victims report the crime. He attributes that to embarrassment and shame.

“They shouldn’t feel embarrassed or ashamed,” Rao said. “These are sophisticated fraudsters who are preying on the human desire for affection. And they are manipulating them using sophisticated technology.”

That technology allows the scammers to establish deeper connections with their victims, like “Sue,” a retiree who says lost her home and nearly $2.5 million to someone she met on Match.com.

“Sue” agreed to speak with CBS under a pseudonym out of fear of still being watched on what she called “the sucker list.” She says the “psychological manipulation” that fraudsters put her through was masqueraded as a love story.

“I Skyped with him. I had no idea that you could fake a Skype,” Sue said. “People say, how can you give money to a stranger? He wasn’t a stranger at that point.”

Rao said law enforcement has tried to counter the faulty assumption that romance scam victims should have known better. There is no single demographic targeted — by some estimates, men make up 40% of victims, and people of all ages and backgrounds have been taken in.

“We have seen very sophisticated individuals become victims,” Rao said. “We’ve had recent examples where physicians, bank analysts who deal with these types of issues in their workplace have been victimized. Anybody could be a victim.”

“I’ve been living a double life”

Kelly Gowe’s crusade began just moments after she raced from Chicago to her mother’s home, three hours west, only to find it empty.

“I just knew, had a gut feeling,” she said.

Kowal was supposed to have lunch that day with her neighbor, Kathy, but canceled just 10 minutes before they were supposed to leave. Kathy said she had seen her in the driveway on the phone with someone.

“We had suspicions of Frank at the beginning,” Kathy said. “But you have to know Laura. She was such a strong woman.”

Gowe searched her mother’s house and found, buried in a filing cabinet, an undated note addressed to her. It said: “I’ve been living a double life this past year. It has left me broke and broken. Yes, it involves Frank, the man I met through online dating. I tried to stop this, many times, but I knew I would end up dead.”

The note left instructions for how to access her mother’s emails.

How it started

After her husband’s death from cancer, Kowal had moved from Chicago to Galena, a small town in northwest Illinois that boasts stunning views from a state park overlooking the Mississippi River and a 19th century house that belonged to Ulysses S. Grant.

She quickly collected a wide circle of friends, playing golf, working at a boutique and traveling to senior centers with her dog Effie, a white poodle with an easy disposition.

Family Photo

“She had all these buckets full in her life, my mom did. But there was this one bucket that was missing,” Gowe said. “And that was this companionship.”

In 2018, she joined Match.com. She chose to meet someone online, just as 3 in 10 Americans have, because she told her daughter it felt safer than meeting someone out at a bar.

Enter “Frank Borg,” a self-described businessman who claimed he was born in Sweden but with roots in the U.S., with whom she connected on the dating site. Frank’s photo showed a trim man in the outdoors, with an angular face and salty hair, mature and fit. He claimed family ties to Iowa, just like Kowal; the loss of a spouse, just like Kowal; and a single adult child, just like Kowal. After a few days on the site, the pair exchanged emails.

“I’m also new to this online dating thing,” he told Laura in his first email to her. “I am an honest and caring person who is very loyal to those I care about.”

The following day they exchanged numbers. “I hope we can always talk on [sic] phone and cherish each other [sic] voice,” he wrote to her.

Over the next 10 days they exchanged stories and Kowal began opening up to him. “Trusting you blindly here. Trust is really big for me,” Kowal wrote.

In total it took 12 days to get from that first email to Kowal returning his affections. “My heart is ready for you!” she wrote, signing off, “Love you, Frank! Your [sic] in my heart forever!”

“Clearly, my mom felt the emotions of feeling loved,” Gowe said. “And I know there’s a lot of people out there saying, ‘Well, how could that happen?’ It could happen to anybody.”

A dramatic rise in scam activity

Kowal’s venture into an online relationship came just as federal law enforcement officials were seeing a dramatic rise in scam activity on dating sites and social media.

“We see from 2017 to 2023 is when we had a sharp increase in romance frauds,” said James C. Barnacle, Jr. who oversees the financial crimes section of the FBI. “Prior to 2017 we didn’t have a significant number of romance fraud complaints in the United States.”

Experts attribute the rise to better technology in hotspots for fraud, like Nigeria and Ghana, and an easier path to moving money electronically. Romance scams had evolved since the days of “Nigerian prince” letters and money wired through Western Union, Barnacle said.

Mark Solomon, president of the International Association of Financial Crime Investigators, said fraudsters had educated themselves. They began sharing scripts and techniques on the dark web and social media sites and Telegram.

“There’s playbooks out there,” Solomon said. “How to commit this crime from A to Z.”

Solomon said law enforcement was caught flat-footed.

“Law enforcement is a little bit behind,” Solomon said. “We have to train more local detectives and investigators, more state, more federal [agents].”

“No other choice”

When local police began investigating Kowal’s disappearance, their missing person alert identified her as being suicidal. It was a misunderstanding, Gowe says, forged in the panicked first hours after her mother had vanished.

In fact, Gowe had begun to find evidence that her mother’s “relationship” with “Frank” had morphed over time. Hundreds of emails show how “Frank” manipulated her, coaxing her into wiring funds to a fake company called Goose Investments. In total she sent $1.5 million.

Initially, their emails had all the language of love. Him telling her he would “never stop loving you.” Her replying: “This is love! Blind trust! Yes, I am the woman who is trusting you.”

But over time, their emails lose the sheen of romance and become more transactional. “Frank” sends emotionless instructions for Kowal to make fake dating profiles on apps like Match.com and Christian Mingle, to open multiple new bank accounts, set up false companies, and eventually, as her savings dwindled, to mortgage her home.

As the nearly two-year relationship went on, Kowal started to express skepticism. In one exchange in May 2019, she emailed him saying she was “struggling.”

“You, and these strangers, are clearly finding out more about me than I know about you through this process,” she wrote, her suspicion rising.

The longer the scheme went on, Gowe found that the trail became confusing, with more and more conversations taken offline. She believes her mother began receiving threats.

“I believe there were threats behind it, or maybe this was her way of recouping the money that she had given them,” Gowe says. “It just really saddens me that it got to that point that ultimately she was participating in illegal behaviors, right? And I believe that she was doing that because she felt like she had to. There was no other choice.”

A body in the Mississippi River

On Aug. 9, 2020, a Missouri State Police marine accident team responded to a report of a body floating in the Mississippi River near Canton, Missouri, hundreds of miles from Galena. Laura Kowal had been found.

Hours later, Kowal’s car was discovered on a boat ramp in a hardscrabble river town in Southern Illinois, more than three hours south of Galena. Police found no glaring sign of foul play..

Lewis County Missouri Sheriff David Parrish told CBS News that investigators at the scene sought to determine, “Did something happen here? Is this more than just a recovery? And based on the investigation we did at the time, primarily through the Marine Division of the Highway Patrol, it appeared that it was a recovery.”

A forensic review of Kowal’s phone shows that it was turned off in the hours before her death. Her last text message to her friend Kathy was, “All is good.”

An autopsy proved inconclusive, ruling Kowal’s death to be from drowning, but giving no further indication about how she wound up in the water. Police, Gowe said, made a snap assumption that her mother died by suicide.

Since her mother was found, Gowe has been troubled by the incongruities of the case. Who was she speaking with on the phone as she left home? How did her car wind up parked on a boat ramp hundreds of miles away? Why, if she took her life, would she do it in a manner that would make it unlikely she would ever be found? And what of the cryptic note — not left on the counter but buried in a drawer — predicting she would wind up dead?

“I have never been ashamed if [a finding of suicide] was the outcome,” Gowe said. “And it’s not because I don’t want to believe that. There would be some closure that would come if we were able to prove that my mom committed suicide. … But do I believe that they have been proactively seeking out evidence in an investigation beyond suicide? No.”

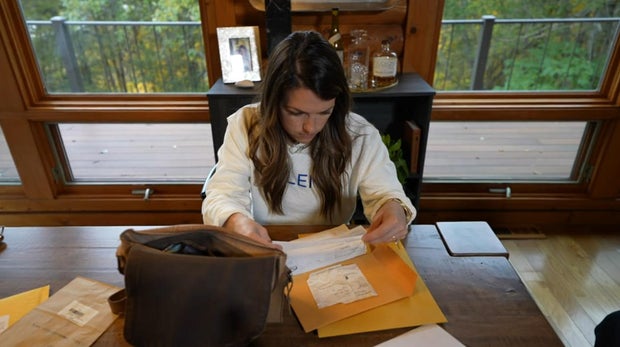

CBS News

Law enforcement has been unable to determine if Kowal was in contact with someone during her drive. They found packaging for a burner phone in her home, but no actual phone. Her Honda Pilot was not a recent enough model to allow them to re-trace her drive through on-board computers. Her last cellphone ping was near the river crossing in Sabula, Iowa, 40 minutes south.

Gowe and her mother’s close friends have sought answers themselves, re-tracing her mother’s likely driving route, collecting surveillance images from that day on the chance of finding evidence Kowal was not alone. So far, she has pursued many leads, but found few answers.

Investigators have been unable to verify the real identity of “Frank” — only that the photos used were stolen from social media of a doctor in Chile, and that the emails actually originated in Ghana.

Match Group said it removed the fraudulent account immediately once it was notified by federal law enforcement, but would not say how long the profile was up on their site, or how many others matched with Frank.

Last year, Gowe left her job and has dedicated herself to share her mother’s story as a cautionary tale and advocate for victims. Earlier this year she spoke to a women’s group in Iowa, urging financial institutions and law enforcement to do more to protect victims.

“I would not be doing her justice,” Gowe said, “if I wasn’t sharing this case and her story to help other victims, and to educate people so that nobody else falls victim to the crime of romance scamming.”

CBS News investigative reporters Pat Milton, Clare Hymes and Alyssa Spady contributed to this report.

If you or someone you know has been affected by a romance scam, please share your story with us at RomanceScams@CBSNews.com