The opinion, delivered 28 years after the suit was filed, was supposed to fund efforts in some of the state’s poorest districts for teacher and principal training, more books and supplies and expanded pre-K.

But those remedies are now in jeopardy as the Supreme Court, with a fresh political makeover, once again considers the case.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

When a trial court ordered the state to spend surplus funds on the remedies, Republican leaders who control the legislature appealed. They argue that the court never had the authority to issue “a sweeping statewide order” based on the claims of the original plaintiffs: five poor, rural districts.

To the districts and equity advocates, however, the move smacks of a political power play. Under the former Democratic majority on the court, the ruling was tight — a 4-3 vote for the districts. Following the November 2022 election, the court flipped to a 5-2 majority in the Republicans’ favor.

If the court overturns the opinion, today’s students would be the “third generation of children since this lawsuit was filed to pass through our state school system without the benefit of relief,” Melanie Dubis, lead attorney for the districts, said during oral arguments in late February. The state, she said, has the “constitutional duty to provide the children the opportunity for a sound basic education.”

Matthew Tilley, the attorney who argued the case for House Speaker Tim Moore and Senate President Pro Tem Phil Berger, said it is his firm’s “policy not to comment on ongoing client cases.”

NC’s Top Court Compels State to Turn Over $800 Million in School Funding Case

It could be months before the court issues an opinion on the case. That leaves districts in the state, which ranks near the bottom nationally in per-student funding, in limbo. But experts suggest the case has implications beyond the education budget. In a state where lawmakers have sued for more power over Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper, and last year overrode 19 of his vetoes, the court’s decision to rehear the case raises questions about whether the legislature is exceeding its authority.

“This case is about having power over the courts,” said Ann McColl, a lawyer who co-founded The Innovation Project, a school leadership network. “The balance of power that helps government function properly is … at stake.”

‘Righting that wrong’

With the 70th anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision ending school segregation this spring, other observers see the conservative court’s decision to reopen Hoke County Board of Education v. North Carolina — also known as the “Leandro” case — as a setback for efforts to address segregation’s legacy.

“It’s important for us as a country to be righting that wrong and to ensure that we invest in schools and districts having high concentrations of students of color,” said Ary Amerikaner, co-founder of Brown’s Promise, a nonprofit promoting integration. “Underfunding of public schools in certain districts and states is deeply connected to racial segregation and racial inequities. That is certainly no different in North Carolina.”

The statewide funding gap between poor and non-poor districts has grown wider in recent years, according to a 2020 report from Public School Forum, a research and advocacy group. School systems without a strong tax base, like the five original plaintiffs, predominantly serve minority students — those who were more likely to fall behind because of the pandemic and need extra help. Meanwhile, districts have turned to for-profit companies to provide virtual teachers and long-term substitutes to fill vacancies as they await the additional funding the remedial plan was supposed to provide.

Exclusive Data: Fueled by Teacher Shortages, ‘Zoom-in-a-Room’ Makes a Comeback

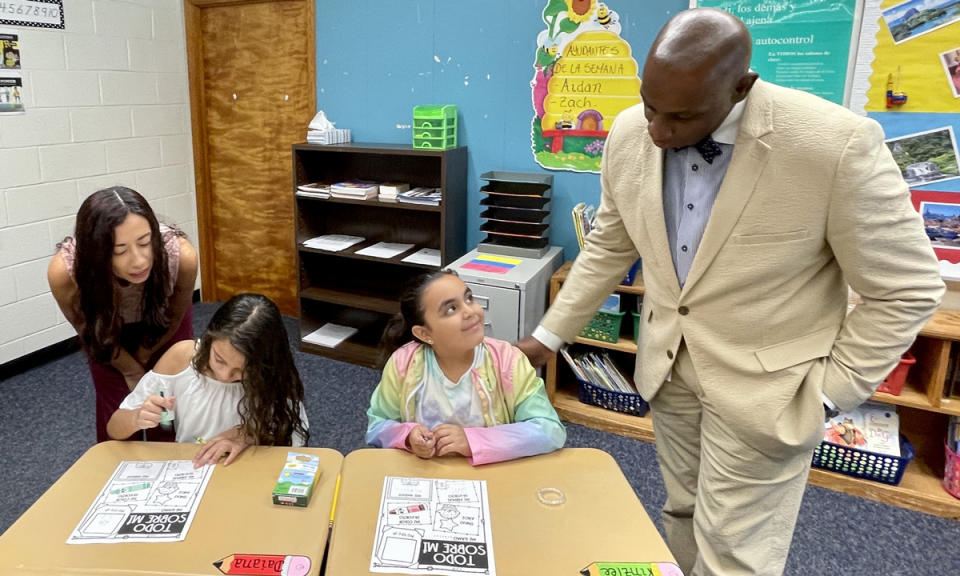

To Anthony Jackson, superintendent of the Chatham County Schools, west of Raleigh, the plan would address some of the growing district’s greatest needs, including more funding for competitive salaries and additional pre-K slots for 4-year-olds on waiting lists.

“It would mean resources to recruit, retain and reward the best teachers and get them in front of our kids,” he said. “It would mean a strong leader standing at the schoolhouse door in every one of our schools.”

Jackson previously served six years as superintendent of Vance County schools, one of the original plaintiff districts. Located next to the Wake County district, the state’s largest, Vance struggles to fill classrooms with qualified staff, Jackson said.

Under the plan, Vance would receive an extra $16 million by 2028, a 39% increase that could pay for 35 more teaching assistants, 47 more nurses and mental health professionals, and 46 more spaces for pre-kindergartners, according to Every Child NC, an advocacy group that calculated the impact on each district.

According to the most recent annual report from an early-childhood education research and advocacy group, the state serves 19% of its 4-year-olds in public pre-K, but no 3-year-olds.

“We’ve got to support parents from the day they have that child. Kids go home for five years and then we expect them all to show up at the schoolhouse door at the same place,” Jackson said. Noting the state’s passage last year of a universal school choice program that provides at least $9,000 per student for private school tuition and other educational expenses, he added, “If we can find the resources for Opportunity Scholarships, I’m sure we could find resources for universal pre-K.”

North Carolina to Launch Education Savings Accounts, With Up to $7,500 Per Child

But others say the plan does not directly address student achievement.

“Will the teachers get paid adequately? Will people be able to go to schools without mold? Those are things that are important, but they’re not about performance,” said Marcus Brandon, executive director of NorthCarolinaCAN, a nonprofit that advocates for school choice. A former Democratic state representative, he said he supports the Leandro plan in principle, but still thinks the court has the authority to throw it out.

During February’s oral arguments, Tilley, who represents legislative leaders, argued that the remedial plan “dictates virtually every aspect of education policy and funding” and that the court’s ruling removed “those decisions … from the democratic process.” He stressed that an earlier court order in 2004 limited the relief to just one county, Hoke, and said the court should not have found a statewide violation.

In her response, Dubis accused the lawmakers of “gamesmanship” and said it’s illogical to apply the solutions only to Hoke, but not to other districts with, for example, similar teacher vacancies.

“It is a system that works on a statewide basis,” she said.

The outcome of the long-running case also rests on a second, but no less significant, matter.

Just months after the 2022 opinion, the new conservative court undercut the decision by ruling, in what McColl called “shadow litigation,” that the state controller can’t transfer surplus funds to pay for the relief. That means that even if the school districts win, it’s likely that funding for the plan would be further delayed.

“That’s what makes this so odd,” McColl said. “Without the ability to enforce a money remedy, these cases just don’t serve a lot of purpose.”

Like McColl, Derek Black, a University of South Carolina law professor and a member of the Brown’s Promise advisory board, has followed the Leandro case for years. He was among the legal scholars who submitted a January amicus brief, arguing that, unlike state legislatures, which often repeal prior laws when the party in power changes, courts are obligated to uphold prior judicial decisions even when they disagree.

The brief noted that over the course of the litigation, both Democratic and Republican justices authored unanimous decisions in the case.

“If overturned, it would be a huge shock to the rule of law,” Black told The 74. “To allow do-overs would mean that litigation would never end and that no judicial decision would ever be binding. I hope and believe that this court understands that.”